How to Renovate in New York City

How to get your renovation approved by the city

When do you need a building permit to renovate in NYC?

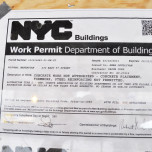

Unless you are doing only minimal updates to your co-op, condo or townhouse, your renovation will likely require a DOB permit––and some co-op and condo boards mandate getting a permit no matter what. As anyone will tell you, it takes time and money to follow DOB’s permitting protocol. Here’s how to tell if you need permits for your renovation--and how to get them.

Renovations that require a permit

There are two general categories of work that falls under DOB permitting:

- Type I: Your renovation requires a major change to the certificate of occupancy, including changing the use of the building from commercial to residential, adding a bathroom or bedroom, or combining apartments.

- Type II: Your renovation requires different trades such as plumbing, electrical and construction, even if there's no change to the certificate of occupancy.

An easy way to think of it is that if you are doing anything that opens up the walls, such as relocating the sink and toilet in a bathroom, or rerouting gas pipes and adding electrical outlets in a kitchen, a DOB permit will be a must.

Same for removing walls, whether structural or not.

It’s always a good idea to start by calling the DOB or visit them in person to get information on what you need, as getting a permit varies on a case-by-case basis. A qualified architect and contractor will also be able to offer guidance.

Note that if you are adding a bedroom, the DOB has strict requirements around dimensions, egress, and natural light and air for making it legal; your architect will be able to advise you (and see links below).

With more than 50,000 square feet renovated in NYC, Bolster understands how to guide New Yorkers through any renovation challenge, from navigating Landmarks to recreating pre-war details, and gives them full visibility into project milestones. "Bolster is the only renovation firm to offer a fixed-price cost up-front. Once we perform due diligence and verify the existing conditions of your property, we absorb unforeseen project costs," says Bolster's CEO and co-founder Anna Karp. Ready to start your renovation? Learn more >>

Renovations that do not need a buildings permit

Generally speaking, a DOB permit isn’t required for “cosmetic” or surface upgrades. This includes painting, wallpapering, and floor resurfacing.

In a bathroom renovation, you would not need a permit for installing new tiles or flooring, lighting, and plumbing fixtures (toilet, tub, sink), so long as those fixtures are staying in the same location.

The same goes for a kitchen redo where you are swapping out appliances, surfaces (countertop and backsplash), fixtures (sink and faucet), and even cabinetry––so long as you are not shifting their placement.

That said, you may still need a Limited Alteration Application (LAA) when modifying or replacing gas or plumbing lines (such as when replacing a tub with a shower), but those can be obtained by a licensed contractor or plumber rather than having to hire an architect or engineer.

Note: Some boards will require you to get a permit even when the DOB would otherwise not mandate that (check with your property manager).

Professional certification alternative

The standard certification process involves filing plans, waiting for a DOB review and subsequent comments or objections, and resolving those issues to obtain final approval.

To avoid a continual logjam, the city gave architects the ability to sign off on their own plans for common home renovations (but not in landmarked buildings or when applying for a new certificate of occupancy). In this self-certification (also known as “professional certification”) process, professionals effectively state that the plans they are filing with the DOB comply with applicable laws, thereby eliminating the need for certification by the city. End result: You can get a permit the same day rather than weeks.

Not all boards allow self-certification though, so be sure to find that out. And some architects may not feel comfortable self-certifying a project, especially if they are unfamiliar with the city’s codes. Keep in mind that one of every five self-certifications are audited (randomly) by the city, and if the DOB finds any issue with the initial plans or the final conditions, it will conduct a full review and can require changes, potentially long after your work has been completed.

If your architect does self-certify your project, make sure they complete the process, which means closing out all the permits when a job is done.

Inspections

During the construction phase, the city will conduct plumbing and electrical inspections to ensure compliance with the filed plans. This can often involve multiple site visits between ConEd and the DOB.

Once all of the construction is complete, a final inspection is conducted in order for the DOB to sign off the job and close the permit.

A contractor can choose to self-certify the final DOB inspections. These are subject to random audit (similar to architect self-certification) and subsequent inspection by the DOB.

Potential problems

Here’s where your final walk-through with your architect or contractor is key in going through a “punch list” of items that need to be addressed before the construction team leaves (and the DOB inspection takes place).

What the DOB will be checking is that all the renovations are code-compliant, which includes seemingly minor things like having enough space between a washer/dryer and the ceiling as well as ADA rules for egress in a bathroom (for example, if you installed larger fixtures without expanding the square footage).

Other problems crop up when the inspections were not completed during various project stages (such as electrical and plumbing), or when the final work deviates from the original plans. In that case your architect or contractor will have to submit revised as-built plans for approval by the DOB.

Another potential approval problem: Illegal work by previous owners.

In reviewing your plans, the DOB might see red flags based on prior work and not only reject the application for a permit but charge you a fine. Then you’ll have to remedy that illegal work before resubmitting new plans (and hoping nothing else turns up).

In other instances the illegal work is discovered by the contractor or subcontractor (say, a gas pipe has been installed without any record of such) during one of the site inspections. In these instances the DOB will stop the work until the problem is resolved, which may involve multiple inspections (especially if it involves a gas line).

You can try to avoid these unpleasant surprises before you buy by making sure your attorney does the requisite due diligence regarding prior alterations. You can even include language in the contract where the seller has to certify that they only did legal renovations.

You would be wise to also look for permits yourself. All permits for work done after 1993 should be on the DOB’s website. For work done before then, ask the co-op or condo board to provide you with their records.

Paying for an architect to join the pre-purchase inspection can also be a good way of avoiding trouble later on especially if you plan to renovate.

Sign-offs

Assuming all the inspections have passed muster, the DOB will officially close the work permits. This is an important step that should not be overlooked. Open permits can pose problems down the line, such as if you (or subsequent buyers) embark on another renovation. You won’t be able to get any new permits until the old ones are closed out, which may not be easy or inexpensive to do—building regulations change all the time. Even though the work was properly completed at that time could now be in violation of newer codes.

Extra dob requirements if you’re renovating in a NYC historic district

If you plan to renovate a co-op, condo, or brownstone in a historic district, you will need approval from the city’s Landmark Preservation Commission (LPC) before you can then proceed with DOB permitting. The regulations and specifications are specific but tend to be applied on a case-by-case basis. And the unpredictable review process can make renovating a historic district property (especially a brownstone) potentially time-consuming and costly. But there’s plenty you will be able do and ways to speed up the process.

Approval process

Permits for work that conforms to LPC rules can be done at the staff level, where your architect and an LPC preservationist will mostly communicate via email. According to the LPC, fully 90 percent of all approvals are handled this way.

What’s more, staff-level permits for interior and some non-visible exterior work can be issued more quickly through its expedited review services.

Permits for work that does not meet the rules––typically extensions and any significant changes to the facade or other features like the stoop or cornices–– require a Certificate of Appropriateness, a much more intensive process that involves a review by the full commission at a public hearing. Before that can happen, you must present your project to your local community board.

Interior renovations

Your architect needs to file plans with the LPC, but generally speaking you have carte blanche to do anything you want on the inside of your brownstone, including gutting it and changing the layout. There are a few exceptions, such as when changing a floor level affects the windows, but those are very rare.

You (and your architect) may prefer to retain historical details on the interior, but there’s nothing stopping you from converting it into an open loft-style dwelling.

Exterior renovations

The LPC will review plans for any “visible” elements with more scrutiny, the goal being to preserve the historic fabric of the neighborhood. This includes items that could be seen from all street-level vantage points, including in front of your house but in a sort of 360-degree sweep that includes the street that’s parallel to yours and might get a glimpse of your brownstone’s rear side.

You will mostly be expected to renovate the exterior to be as close to the original appearance as possible. This can include restoring or replacing the actual brownstone facade and any architectural details like cornices. The LPC also has specs for front door types and paint colors; same for the stoop and railings.

For the most part, these renovations can be handled at the staff level unless you are proposing a significant alteration, such as replacing brownstone with limestone or red brick (it has happened).

Windows

The LPC is notoriously stringent about the steps you will need to take to find replacements with the same profile and sight lines and operation––and there are hefty costs in working with a sanctioned window company and skilled contractors. Exceptions have been made, but not without significant time and expense in convincing the commission to give the green light through a full review.

As for adding a new window? Never in the front but maybe in the back. Plenty of brownstones have been updated to have walls of glass on the ground level leading out to the garden, but the LPC has shot down expansive windows on an upper floor that would be visible from the street.

Extensions

The level of scrutiny for vertical or horizontal additions tends to be extremely thorough. There’s just too much risk for setting precedent. Expect to add at least three to six months to the approval process.

Any rooftop addition must be completely non-visible from the street, usually by way of a 15-foot set-back. (The same goes for putting new mechanical equipment on the roof.) Your architect will have to submit much documentation to prove your case, complete with a painted mock-up of the structure and photos from all different perspectives.

You have a bit more leeways with rear extensions, so long as they comply with zoning ordinances, which deal with height, depth, and total square footage. The LPC also generally requires these additions be at least two stories shorter than the brownstone, or matches what’s the norm in the particular historic district.

But besides these restrictions, additions need not be in the style of the original brownstone. Indeed many architects find it easier to get one approved if it is ultra-modern rather than some faux period piece. That means you might be able to get a glass cube on top or in the back.

What’s an expeditor, when do you need one, and how much will it cost?

Expeditors (or what the DOB calls “filing representatives”) are experts when it comes to NYC renovations: They're required to keep abreast of all the changes to code, and they also know which questions to ask, how to fill in the forms, and what you'll pay in fees. They also do all the legwork, visiting the DOB in person and standing in lines and all the other running around that’s part and parcel of getting permits through the city’s infamously complicated system.

What your expeditor should be doing

Expeditors act as liaisons between you and the DOB and can help figure out which permits you need, as well as facilitate the paperwork. Before you submit a permit application to the DOB, an expeditor will review your reno plans to make sure they follow the city’s construction codes. The expeditor will also make sure to get all the signatories, which include you, the architect, contractor, and property manager, and sometimes the board president. Then, while the department is processing your application, they gather all the necessary checklists and signatures (from building owners, architects, and so on) and field the DOB's queries.

When it comes time to get the DOB to sign off on your project, an expeditor can help the process along, including managing the third-party inspections and additional documentation that are often required.

The expeditor can also handle the final paperwork and sign-offs for your architect or contractor. The last thing you want is outstanding "open items" from your reno that tie up an eventual sale of your apartment.

When an expeditor is helpful

Using an expediter is no guarantee that your permit application process will be speedy. But it does increase the chance that you'll get the approval you need faster than if you navigated the bureaucracy solo.

This is particularly true if you are planning a gut-renovation of a brownstone or apartment, where by definition you are going to be dealing with multiple permits and subcontractors. There’s just a ton of “I”s to dot here, with lots of running back and forth and in between.

And most architects will rely on expeditors when working on a building in a historic district, as dealing with the Landmarks Preservation Commission adds a whole other level of approvals (and additional months) to an already labor-intensive process.

How to hire one

Because an expeditor takes on tasks usually handled by your project team, your architect or contractor will be the one to do the hiring. Anyone with experience renovating in NYC will know where to find reputable expeditors; some architectural and engineer firms even have them on staff. You may still want to make sure the expeditor is registered with the DOB and has a clean record.

Cost of hiring an expeditor

Expect to pay an expeditor anywhere from $2,000 to $3,000 for a complete reno package (more for a landmarks project), plus miscellaneous fees, per permit process. Contractor permits are more in the range of $400 to $600 per permit. Though these upfront costs may seem steep, hiring an expeditor is well worth it, and you will save time and money (and frustration) in the long run.