Neighborhood Intel

Go behind the exclusive gates of the Dakota, the city's first luxury apartment building

The Central Park West building made famous by John Lennon and Yoko Ono is the subject of its first full-length history, called The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building. Written by historian Andrew Alpern and to be released later this month, the book takes an in-depth look at the building's beginnings in the 1880s, and its developer, Edward Clark, and architect, Henry J. Hardenbergh.

As home to some of the city's biggest boldface names, the Dakota would no doubt be a font of serious gossip. Over the years icons like Lennon, Lauren Bacall and Roberta Flack resided there, and when we think about the building, it is hard not to picture its cinematic cameos in Rosemary’s Baby and Vanilla Sky. But aside from a brief mention of the pictorial spread of Nureyev’s 3,300 square-foot-pied a terre in the New York Times Sunday Magazine in 1993 and a list of first residents, there is nary a mention of any of the more exciting happenings related to the building such as high-profile lawsuits, or its place in literature and cinema.

No such luck: The Dakota is, instead, a serious, but equally compelling, book that chronicles all about the nuts and bolts of how the building at 1 West 72nd Street came about: its construction; how it changed the face of Manhattan’s Upper West Side and its renovations over the years. (It's more history class than TMZ.) Those looking for discussion on figurative Dakota “dirt” more than literal should look elsewhere.

Nevertheless, there are some interesting tidbits for consumption:

The Dakota changed how the one percent lived

Until the Dakota was constructed in 1884, the norm in New York City was for wealthy residents to live in freestanding homes. Around the time the Dakota was being constructed, hotel residences were popping up that offered an alternative.

The Dakota was the first of its kind, a multi-family dwelling for the well-heeled in which residents lived in separate apartments but shared amenities, such as a dining and food areas that prepared meals to be consumed in apartments. There was a section devoted to laundry that servants apparently did for residents.

The west façade of the Dakota, circa 1889. Office for Metropolitan History

Upstairs, downstairs living personified

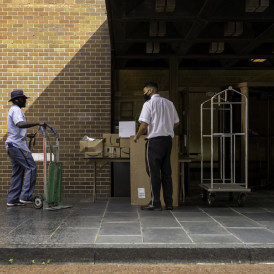

To keep servants and deliveries from impeding residents’ comfort, the building was set up to allow servants to use the sub-level basement area to enter and deliveries to be made, while residents used the front first floor entrance. The original gates locked at midnight, after which residents needed to ring a bell for entry.

Building amenities were important then, too

The residents’ apartments were on the middle floors. The eighth and ninth floors were reserved for sleeping and bathroom facilities for servants (and for laundry). A 10th floor was dedicated to a children's play area, laundry drying, and water tanks. The first floor was reserved for private dining facilities.

Sky-high prices even back then

The land for the building was purchased by Edward Clark who had clear advantages over other developers at the time because he used his own money and didn’t need investors. He bought the plot on which the Dakota stands for $250,000; building construction costs were $2 million and took 4 years (1880 to 1884).

Apartments then ranged from $1,500 to $5,500 a year. Today, according to Streeteasy, active sales listings range in price from $3.6 million to $23.5 million.

A woodcut accompanying a long article about the building in the September 10 1884 issue of The Daily Graphic, reporting on the completed Dakota.

Status changes

In 1961 ownership passed from the Clark family to a co-operative corporation. In 1969, the Dakota got landmark status by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Keeping the place like new

While under the care of the Clarks, the building fell into disrepair, and in 1974 the co-op voted to fix much of it, including elevators, to the tune of $500,000, which cost an assessment of $5,000 per apartment.

Twenty years later, the Board finally voted to have the facade cleaned and 2,000 windows fixed. The $5 million in renovations then came to $500,000 per apartment. All fireplaces were made functional again. “Tiny electronic cameras were threaded down each of the hundreds of chimney flues (a separate one for each fireplace) and the problem areas were recorded on a special set of drawings,” Alpern writes. Where there were “danger spots,” the flues were completely rebuilt by hand. Skilled contractors had to painstakingly break into walls to reach them and then replaster and restore each room.

In 2004 the central courtyard was renovated and the surface was replaced because the steel structure had corroded. It took a year to complete.

Related:

Brick Underground articles occasionally include the expertise of, or information about, advertising partners when relevant to the story. We will never promote an advertiser's product without making the relationship clear to our readers.