The tragic backstories behind 5 major NYC safety laws

Unless you happen to spend your downtime leafing through the city's building codes for light reading, safety regulations are a lot like our insurance policies: We tend not to give them much thought until disaster strikes. Then, they can be the only thing standing between us and grievous injuries (or worse).

And as evidenced by the crackdown on DIY spaces after the fire at Oakland's Ghost Ship warehouse, city safety rules are an ever-evolving work in progress. From the turn-of-the-century Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire (which led to the creation of numerous labor and safety laws), to the 1990 Happyland Fire (which changed the requirements for public gathering spaces), to 9/11 (which led to increased stairwell requirements in skyscrapers, among other regulations), many of the laws keeping our apartments safe have been drafted in response to disastrous events or incidents.

"It's a shame that all these laws are reactive to bad incidents, but the good that comes out of it is that they make much better safety provisions," says architect Michael Zenreich. "One would prefer if we were proactive with these things, but the reality is that new requirements add to cost, and everyone is sort of just waiting for something bad to happen before they change the law."

Below, five now-commonplace New York safety rules and regulations that were born out of necessity:

The 1867 and 1901 Tenement Acts

Though we now take for granted certain building requirements in our apartments—for instance, the existence of fire escapes and the stipulation that every bedroom must include a window—back in 19th-century New York, many such mandates were far from given. That all changed with the Tenement Act, which was first introduced in 1867, amended in 1879, and updated into its more modern form in 1901.

Before these laws came into place, it took a series of unsettling events for the city to sit up and pay attention, including the 1863 draft riots, a violent series of clashes in response to a Civil War draft that disproportionately affected poor New Yorkers, as wealthier citizens were able to buy their way out. (The Bowery Boys have a whole episode about the riots here.)

"Though the immediate spark for the riots was the draft itself, many of the protesters were working class and poor New Yorkers, who were dissatisfied with their living conditions," says Dave Favaloro, director of curatorial affairs the Tenement Museum. "There was an understanding that their living environment had made some contribution to what had happened." Since the riots were in part a referendum on the low quality of life for poor New Yorkers, the quality (or lack thereof) of their housing options was thought to be a key source of the discontent.

Cramped, poorly lit, and badly ventilated tenements also posed pressing health issues. "One of the more endemic public health issues was tuberculosis," says Favaloro. "And even before officials understood that it was caused by bacteria, they understood that it flourished in unventilated quarters." Hence, new requirements stipulating that every bedroom have a window opening to plain air; that buildings must have outdoor courtyards for garbage storage (to prevent trash from being tossed into air shafts); and that new buildings feature indoor toilets.

Benevolence was definitely at work when it came to overhauling city rules, but containment mattered, too, and lawmakers were very concerned about what an overcrowded environment like the Lower East Side tenements meant for the whole city, Favaloro adds. "For instance, they wanted to prevent cholera from ravaging that population, but also didn't want it engulfing the entire city."

Facade inspections

Don't let its dry moniker fool you: The Facade Inspection Safety Program (also known as Local Law 11) serves a crucial purpose for citywide safety, requiring owners of buildings above six stories to have their facades regularly inspected, the better to prevent any debris or masonry from shaking loose, falling from great heights, and injuring pedestrians below.

However, it's a relatively recent requirement, and arose in response to a 1979 incident, in which a 21-year-old Barnard student was killed by a chunk of masonry that fell from a building near campus. "After that, Local Law 10 was enacted in 1980, though it was fairly vague, and didn't require thorough investigation," says Zenreich. In 1998, a stricter new version known as Local Law 11 was passed, and also included requirements for the inspection of balconies, in addition to more detailed requirements calling for the inspection of a building's entire envelope by a registered architect or professional engineer.

Window guard requirements

Requirements for window guards didn't arise due to one specific precipitating incident, but rather, a series of them. In 1976, when window guard laws came into effect, 217 children died from falling out of windows, compared to just six such accidents in 2013, as we wrote back in 2015, when activist and politician Charlotte Spiegel, who spearheaded the initiate, died.

The rules, which require landlords to install and maintain window guards in apartments occupied by children under 10, came as a result of a campaign headed by Spiegel entitled "Children Can't Fly," per the New York Times. As with many safety laws, New York's were the first of their kind in the nation, and have since inspired similar rules nationwide.

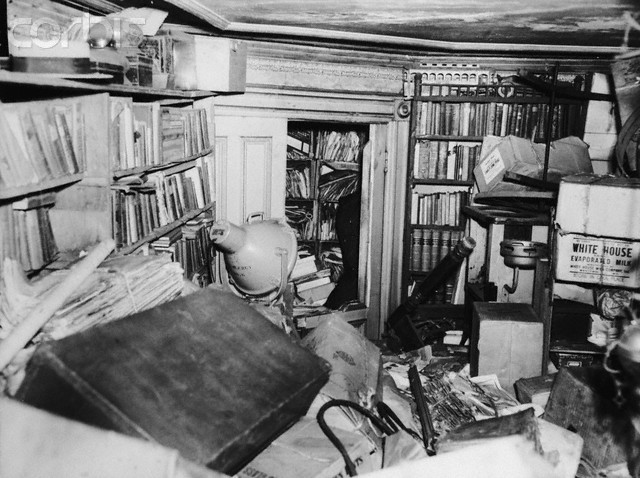

The crackdown on temporary walls

Technically, temporary walls put in without Department of Buildings approval have always been illegal in New York City. However, for years, landlords and building inspectors were happy to look the other way as cash-strapped renters used them to subdivide up their apartments, as we've written previously.

This all changed after a 2005 fire, in which firefighters found themselves trapped in an apartment that had been illegally subdivided and forced to jump from a window. As the Times reported in 2010, the fire eventually led to manslaughter charges against the building owner, which in turn led both city inspectors and building owners to crack down on the practice, refusing tenants' plans to put up these walls and insisting that existing ones be taken down. It's still possible to put up temporary walls in certain buildings, but your newly-created room still has to meet legal size requirements and include a window—all requirements laid out by the aforementioned Tenement Act.

New gas safety legislation

The last several years have seen several disturbing (and fatal) gas explosions around the city, from the 2015 East Village explosion to a similar 2014 blast in East Harlem. This, in turn, has led to increased caution by both the city and Con Ed over any potential gas issues.

"All of us who work in housing are finding, anecdotally, that there are so many people who don't have gas, because as soon as there's a leak at all, they shut down all the gas," says attorney Cathy Grad. "There are new city rules in place that are onerous for buildings to follow, and not incorrectly so." (In December of last year, de Blasio signed into law a new package of legislation relating to gas safety, including requirements for inspections of building gas piping systems every five years, and for any work on gas piping system to be done by a licensed, Buildings Department-approved professional.)

"Right now, there are so many buildings [that don't meet the requirements], and not an adequate number of inspectors to go out and get the gas turned back on," notes Grad. Indeed, we've heard multiple stories of gas in even higher-end buildings being shut off for months at a time.

Hopefully, the process will get smoothed out in the next few years, and soon, we'll take our safer gas hookups for granted, right along with our smoke detectors and fire escapes.

You Might Also Like