Lights out: New York City's ghost apartments multiply

The number of apartments being used as pieds-à-terre and short-term vacation rentals in New York City has spiked by over 20,000 in the last three years, and such apartments now make up 2.1 percent of all housing in New York City, according to census data recently released by the city.

The number of apartments listed on the most recent Housing and Vacancy Survey as vacant because of "seasonal, recreational, or occasional use" is now 74,945. This is the highest since the Regional Plan Association started keeping track in 1991 and, as the group's director of community planning Moses Gates notes, more than enough to house the city's entire homeless population. A Department of Housing Preservation and Development spokesman says that the agency can't parse from the data how many of these 75,000 apartments are being rented out on sites like Airbnb versus how many are being used as pieds-à-terre, and indeed there may be some overlap. Still, it's clear that the gain of 69,000 newly built apartments since 2014 is dampened by the simultaneous removal from of nearly a third of that number of apartments the sales and traditional rental markets.

The case for a pied-à-terre tax

Gates argues that the numbers show the urgent need for the city to create a pied-à-terre tax, so that wealthy people have incentives to sell their apartments or rent them to full-time tenants rather than keeping them empty or occasionally renting them to tourists.

"You're taking housing off the market during a housing emergency," he says. "That should be good enough" for the city to take action. Pied-à-terre owners, he adds, are "not paying city income taxes, but you're using city services to protect your tax investment."

Spokespeople for the Mayor's Office say Mayor de Blasio supports a pied-à-terre tax but that a 2015 Supreme Court ruling on double taxation presents a legal barrier.

Short-term vacation rentals make the pied-à-terre a more financially attractive proposition

In addition to the total number of pieds-à-terre and vacation rentals growing to a record high, Gates says the latest census figures are unusual because the total number of pieds-à-terre typically shrinks during times of economic growth, whereas it grew during the one from 2014 to 2017. Critics of Airbnb and other short-term vacation rental sites say that the platforms' growing popularity could explain the increase. And a real estate market expert says the trend could well be driving up rents and sale prices.

"I think it has an impact on the existing housing stock by taking units offline," appraiser Jonathan Miller of the firm Miller Samuel says of investors and pied-à-terre owners turning to Airbnb. Also, he adds, for some people, short-term rentals are "a tremendous revenue source," so when it comes to selling apartments, "it could change the way we value these units. Because the actual rental rate [for short-term rentals] is higher per square foot."

Darkness in the middle of town

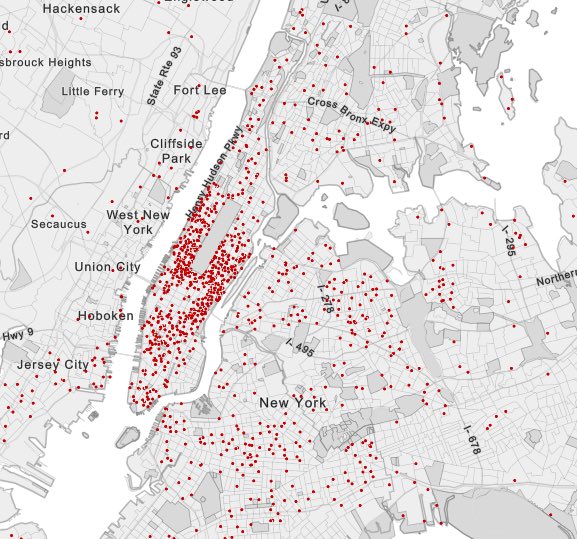

The growth of pieds-à-terre has largely been concentrated in Manhattan, according to market watchers, and activist studies have shown that Airbnb listings are primarily in gentrifying neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn. In neighborhoods where large numbers of apartments are being left empty for much of the year, skyscrapers can become ghost towers, mostly dark at night, with few actual residents on each floor.

"Any New York street where many apartments on the street are pied-à-terres, there’s no business on the block," says Upper West Side state Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal. "No one frequents the retail, or not as many as would if there were people actually living there. And it buys up units that maybe a New Yorker would otherwise be able to afford."

Residents of buildings with short-term vacation rentals, on the other hand, can be forced to live with loud parties, propped-open doors, and even violence and prostitution.

Census data mapped on the site Social Explorer shows that census tracts with 100 or more apartments that are vacant and not for rent or sale are concentrated in Manhattan below 96th Street.

In 2014, the New York Times found that in a three-block stretch of Midtown, 285 of 496 apartments are vacant at least 10 months a year, a trend observers attributed in part to foreign buyers socking away cash in condos. Short-term vacation rentals present one option for offsetting the costs of holding onto an otherwise rarely occupied apartment, though running one could be tricky in a building with a doorman.

Renting out an extra room vs. listing a whole apartment

Under New York City law, it's currently illegal to rent an apartment in a multi-family building for fewer than 30 days if the owner is not home. And yet, a cursory search on Airbnb for upcoming listings for four nights, filtered to include only "Entire Place," i.e. whole apartment listings, returns hundreds of results. Rosenthal introduced a bill last year that would require short-term rental sites to publish host contact information and apartment addresses with each listing, which would make it much easier for city inspectors to root out illegal listings.

Rosenthal tells us that the latest figures show what she's said all along about illegal hotels: "Gentrification is sped up in neighborhoods where there are a lot of Airbnb rentals. The impact on our housing stock is devastating. It hurts communities, it hurts residents, it drives up rents. It creates safety and quality-of-life issues."

Airbnb defends itself

An Airbnb spokeswoman downplayed the absentee investors who use the platform, saying many hosts are working New Yorkers who supplement their income with the platform, and that Airbnb workers have weeded out thousands of listings posted by hosts juggling multiple apartments. Citing a tech industry trade group study, she argued that it's actually hotels that are driving up the cost of living in New York. The study she refers to claims that a comparatively few 398 apartments were lost in hotel conversions from 2010 to 2016.

Airbnb is currently lobbying for another state law, which the company reportedly helped Greenpoint Assemblyman Joe Lentol write. The Lentol bill would create a registration system for Airbnb hosts and limit each host to a single listing, but would legalize less-than 30-day whole-unit listings.

“Airbnb supports legislation that would finally allow enforcement to focus on illegal hotel operators while protecting regular New Yorkers who are trying to make some extra money to live in a city that gets more expensive by the year—in part due to the loss of viable housing stock to hotel development," Airbnb New York policy head Josh Meltzer says in a written statement. "This comprehensive legislation being considered in Albany would also protect public safety and generate $100 million in new tax revenue for New York—and all while allowing responsible hosts to continue to share their home."

Rosenthal took in $12,900 in campaign contributions from hotel unions in 2016, and Airbnb has attributed much of its opposition to the hotel industry, though it didn't specifically single Rosenthal out here. Rosenthal says that any suggestion that she opposes Airbnb because of the donations is "frankly insulting," and notes that her advocacy for affordable housing and against illegal hotels long predates Airbnb's arrival in New York.

What's next in the fight over vacation rentals

Writer Tom Cayler came to be a citizen watchdog of illegal hotels following a drawn-out battle to shut down an illicit vacation rental in his Hell's Kitchen loft building in the 2000s. Cayler says that he and fellow activists plan to lobby for Rosenthal's bill and, longer-term, watch how recently passed regulatory schemes play out in San Francisco and Toronto. San Francisco, he notes, had its Airbnb listings cut in half after the city required hosts to register with the city, with violations punishable by a fine of Airbnb itself. In 2016, Airbnb dropped a New York lawsuit over new regulations after assurances from the city that only hosts, and not the company, would face fines for illegal listings.

"You can’t trust 'em any further than you can throw a lollipop," Cayler says of the tech giant. Whatever regulations legislators come up with, he says, "You know damn well that they will find a way to get around it, because that’s how they make their money. They’re making huge amounts of money by convincing people to do illegal things."

Airbnb made a reported $93 million in profit last year, and executives and investors are currently battling over whether to take the company public.

The typical New Yorker, meanwhile, is officially "rent-burdened" by official standards, paying more than 30 percent of her income in rent. About 3 in 10 New Yorkers pay more than half of their household income in rent, according to the data released last week. These figures are unchanged since 2011. A record 63,000 New Yorkers slept in homeless shelters in January of this year.

You Might Also Like