Is your building rent-stabilized? You should find out

iStock

A fight over the rent-stabilization status of the apartments in a Brooklyn Heights building owned by Jared Kushner's family business could hold lessons for tenants looking to figure out whether their apartments have been improperly deregulated.

On Tuesday, a group of tenants at Kushner Companies' building 89 Hicks Street sued in Brooklyn Supreme Court, alleging that they are being over-charged for what should be rent-stabilized apartments. They brought their lawsuit with the help of the group Housing Rights Initiative (HRI) and the law firm Newman Ferrara. To establish that their rents were allegedly too high, HRI used some nifty research tricks to look closely at the building's history, then compared notes with the tenants, who accessed detailed records about their apartments.

We talked to Aaron Carr of HRI about how they did it, and what tenants might do if they find themselves in a similar situation.

How can I find out the rent-stabilization status of my apartment?

Whether or not your landlord has issued you a rent-stabilized lease, it's a good idea to research the rent-stabilization status of your apartment, because nearly half of all apartments in the city are stabilized. Even if your landlord says your apartment is market-rate, it may not be, and much of the burden of figuring out when an apartment is improperly deregulated is on the tenant.

First, some rules of thumb: If your building was built before 1974 and has six or more units—try StreetEasy for this information—it is likely stabilized.

For an at-a-glance look at whether your building's owner has registered your address with the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR), the rent regulation enforcement agency, since 1993, you can type in your address on this city website, and look at the top of the page for a message in red when the building profile comes up. If your building has been registered as stabilized in the last few decades, there's a good chance it's stabilized now.

Whether or not your individual apartment has since been deregulated by surpassing a rent cap introduced in the 1990s is another matter. To look into this, you'll need to get the rent history for your apartment, which shows each time the landlord increased the rent for your unit, and the reasons they gave. This document holds the key to most individual apartment rent challenges. DHCR has a walk-through for the process of requesting your rent history, but the website amirentstabilized.com has probably the most user-friendly guide.

(For our full guide to rent-stabilized apartments, click here.)

Once you get your rent history in the mail, you'll want a lawyer to look it over to fully understand your options, but if it shows the rent increasing for no reason (typically, landlords can increase rents based on the rate set annually by the city Rent Guidelines Board, percentages of claimed improvements to the apartment and the building, and, since the '90s, by 20 percent whenever an apartment is vacated), or the apartment ceasing to be registered as stabilized with no corresponding rationale, that is the most obvious sign that something is amiss. It's more thorny to prove that the owner inflated renovation costs, but it's not impossible.

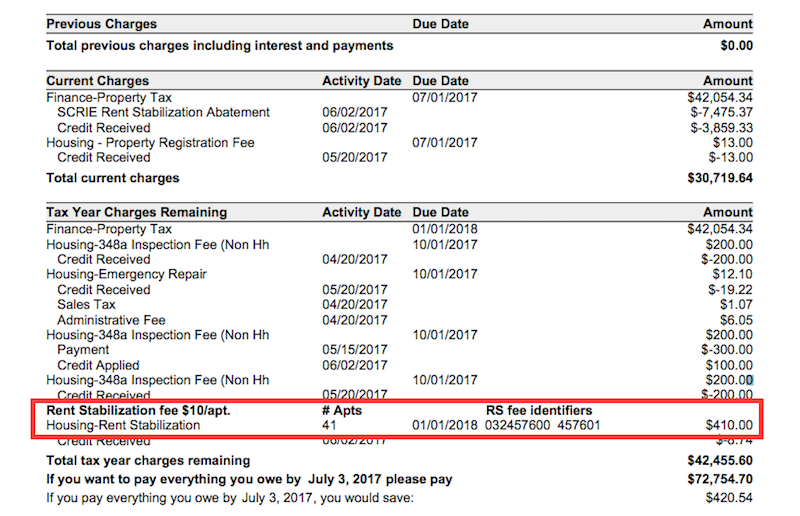

Another avenue of research is the building's tax records. DHCR is notoriously un-forthcoming about the stabilization status of apartments besides the one you live in, but landlords have to include certain relevant information on their tax forms each year. Specifically, if the building is subject to 421-a, J-51, or some other tax break program that comes with an affordability/regulation requirement, that will show up on the tax bill. Similarly, building owners have to pay a surcharge of $10 per rent-stabilized apartment, and that too is reflected on the bill, like in the example below.

To look up the tax bill for your building, first you need the building's block and lot number, a non-address identifier that the city uses. You can find this by searching your address at the city tax map here and clicking "Show Additional Information," then "Building & Property Information." With the block and lot number handy, navigate to the city property tax website here, and type it in. The tax bills here are how the Housing Rights Initiative was able to establish that Kushner Companies listed just five apartments as rent-stabilized in 2014, and now lists none. By cross-referencing these records with the rent histories of tenants, Carr says they've found proof that the developer is failing to meet its obligations on multiple fronts.

If a building used to be stabilized and an owner suddenly stopped reporting the apartments in his taxes, or if he is collecting tax breaks that require apartments to be rent-stabilized while not providing stabilized leases, you too might have a case.

How can I challenge my rent?

Again, ideally you would consult with a housing lawyer before proceeding. As an individual renter, you can use DHCR's administrative process for rent overcharge challenges. You can initiate a rent overcharge complaint by filling out the form here.

That said, there's strength in numbers, and if you suspect based on your research that the issues you're facing are building-wide, consider forming a tenants' association. Organization within your building, in addition to adding leverage over your landlord, also increases the likelihood that a nonprofit organization such as the Urban Justice Center, the Legal Aid Society, or Legal Services NYC might assist you in a legal campaign to affirmatively challenge your rent and conditions. These organizations are worked to the bone in the current affordability crisis, though, so it may also make sense to pool resources and find a good private lawyer as a building. A class-action lawsuit is a more organizing-intensive project that comes with its own set of pros and cons—the one big downside being that the whole group can succeed or fail where one tenant may have had better odds going it alone.

"One of the reasons why we always do it as a class-action is a community perspective: we’re in an affordable housing crisis," Carr says of his group's approach. "Hundreds of thousands of units have been deregulated in the decades since vacancy decontrol. With a class action, you have a few people representing the whole, and it’s a way of preserving that larger number of units and keeping them stabilized."

Also, he notes, lawyers often pursue class action suits for a share of the money in the event of a victory, meaning tenants don't have to pay up front. "When you do it as a class-action lawsuit, tenants don’t have to pay anything out of pocket, so it’s available to tenants at any income level," Carr says.

As great as the potential upsides of litigation may be—cheaper rent, cash back plus damages, and the grudging respect of your landlord—there is also the potential for losing. In non-class-actions, this can mean being on the hook for legal bills, and/or being put on the dreaded tenant blacklist. That said, according to Carr, "This is an opportunity for [tenants] to work with their neighbors and take back what was stolen from them. There’s a lot of community value to this. Obviously the rent reductions and damages are incredibly important in an affordable housing crisis, but this is also a way of bringing the community together, which is invaluable."

For our guide to starting a tenant association in your building, click here.

And for a stark visualization of New York City's vanishing rent-stabilized housing stock, including a clickable feature that will help if you're trying to research your building, here is the loss of rent-stabilized units as reported by landlords to the Finance Department in tax bills from 2007-2014.

You Might Also Like