5 fascinating facts we learned at the Museum of the City of New York's new exhibit on zoning

Wurts Bros., First Avenue between East 30th Street and East 33rd Street. Kips Bay Plaza Apartments, 1966

Museum of the City of New York, Wurts Bros. Collection, Gift of Richard Wurts, X2010.7.2.13688

While zoning might sound like a dry issue best left to urban planners, in reality, this particular realm of policy is anything but dull, as anyone who's ever been to a contentious neighborhood rezoning meeting can tell you. (Lest we forget the Williamsburg waterfront rezoning of 2005, which arguably changed the entire character of the neighborhood.)

In an effort to demystify the world of zoning for New Yorkers, the Museum of the City of New York just launched Mastering the Metropolis: New York Zoning 1916—2016, a new exhibition that looks at the city's very first zoning laws (passed in the early 20th century), how they've shifted to suit the times, and what they mean for our current era of booming development and dwindling affordability.

Below, five things we learned when we stopped by the museum last week for a sneak peek:

If you have open spaces in your neighborhood (instead of wall-to-wall buildings), you have zoning laws to thank

Coming on the heels of a burst of development, New York's first 1916 zoning ordinance was the first of its kind in the United States, regulating types of use (residential, industrial, etc.) as well as density of development (including height). "The idea was to create a little more breathing space," explains the exhibit's associate curator Eric Goldwyn. "There had been discussions about zoning in the city prior to 1916, but the end of the 19th century saw a big building boom, with many companies making their headquarters in Manhattan. And during a frothy real estate market, it's harder to get new regulations pushed through."

However, a downturn in the lead-up to World War I created a more hospitable climate for zoning, right when city officials realized they needed to regulate the market to accommodate the huge influx of immigrants coming into the city.

To prevent tall buildings from blocking natural light on the streets, zoning required buildings to have "setbacks," which meant they could be a certain area on the ground level, but had to shrink in size the taller they got. (They typically have a layered, wedding-cake look; see below for examples.)

1960s planners were worried about making the city *more* like the suburbs

While zoning laws have been continuously updated over time, the next major amendment to city zoning happened in 1961, and among the chief concerns was ensuring that the city stayed competitive with the increasingly-popular suburbs. This meant creating requirements for parking spaces, as cars became a day-to-day part of American life. The amendment also zoned certain city neighborhoods to preserve their residential, suburban character.

"Staten Island is a good example," says Goldwyn. "It was not very developed, but new zoning [stipulated that] instead of allowing for the possibility of higher development, it would be zoned as single-family, with winding streets and planned development of residential units."

Zoning and architecture trends go hand in hand

Mid-century architecture trends were part of the impetus for the 1961 rezoning, which allowed buildings to rise higher, without setbacks, if they took up less square footage on their lot. "Buildings with no setbacks and large parks or plazas were getting trendy, and people wanted those types of buildings," explains Goldwyn. "New York is leading the way in modernity, so you want buildings that reflect modern architecture, and the code had to be updated to reflect it. Developers were willing to sacrifice their square footage to have this public plaza."

Though the choice was dictated by design at the time, these buildings provide an interesting precursor to current zoning requirements, which often require builders of major developments to provide a certain amount of public space or other civic service. (This is also a trade-off developers sometimes offer on their own, both for an improved public image and the sake of services for their residents.)

NYC tried to save its industrial neighborhoods, to no avail

Before neighborhoods full of factory production and industrial jobs, which were rapidly leaving the city by 1961, became ultra-gentrified hubs of lofts and warehouses packed with artists, New York planners did make a good-faith effort to keep them afloat.

"Industry was moving outside of the city, so planners believed they needed to zone more industrial land to be competitive," Goldwyn tells us. "Unfortunately, industry left the city anyway, since those companies wanted more space and cheaper rents, and New York couldn't compete in that regard."

Hence the development of places like Soho, which was zoned industrial but fell into disuse with high vacancy rates. Later, artists started moving into lofts, which ultimately led to the creation of "Loft Laws" that could convert these buildings into residential use. "Williamsburg is another great example of this," says Goldwyn. NYC neighborhoods are nothing if not adaptive.

Zoning updates are more prevalent than ever in modern-day NYC

In fairness, we kind of already knew this one, but putting it in the context of a century's worth of urban development throws into sharp perspective just how much our city has evolved over the past 20 years. Much of this is the work of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who was active in changing zoning to encourage development—his fingerprints are even on the rezoning of East New York that's currently underway.

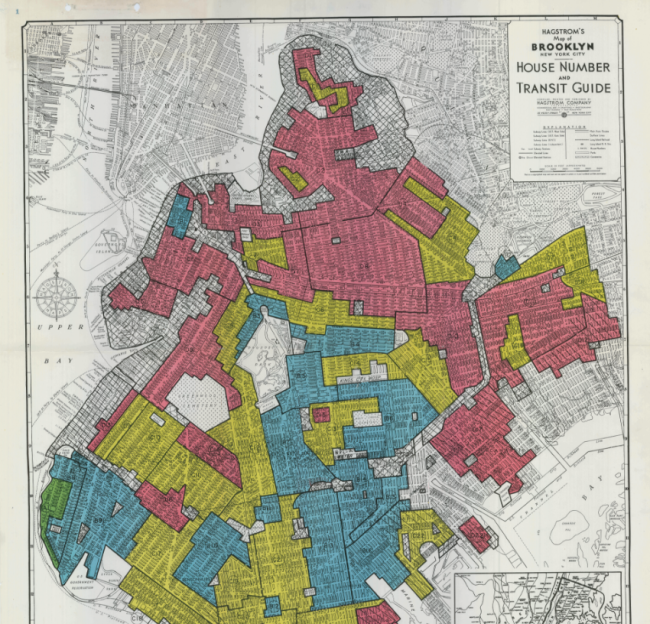

This is as much of a hot-button issue as ever, and Goldwyn notes that "upzonings" allowing for more development tend to be more common in lower-income areas, while "downzonings" (such as the creation of landmarked districts) are more common in affluent, predominantly white areas. Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, which creates so-called "80/20" buidings is also a big part of the picture. But even in its imperfections and tendency towards unintended consequences, New York's zoning rules are a good reflection of the city itself, always moving forward to the next big thing.

You Might Also Like