Why does infrastructure lag so far behind gentrification?

As the city continues to undergo its seemingly unstoppable transformation, bringing change to farther and farther neighborhoods, one question remains: Why are so many basic services near-non-existent in places where housing prices have already shot through the roof?

For instance, it's no secret that many of New York's so-called "emerging" neighborhoods are food deserts, where residents have limited to no access to quality groceries or fresh produce. And with markets shutting down all over the city, the problem's only getting worse. The same is also often true of other day-to-day necessities, such as drug stores, pharmacies, and banks, as well as city services like street-sweeping or snow-plowing. (As one friend in Bed-Stuy put it, "There are five new coffee shops near my apartment, but nowhere to pick up a prescription or buy fresh fruit.")

In many cases, the reason for the disparity depends on the particulars of a given neighborhood, from the zoning to the physical size of the buildings to outright political and institutional neglect. "There are two types of neighborhoods that gentrify," says Corcoran agent Karen Kemp. "There are areas that already have a residential population, and businesses that cater to that demographic, and neighborhoods like Williamsburg that were primarily industrial, so didn't have any existing services for a residential population."

"Every neighborhood is kind of different," concurs David Maundrell, executive vice president of new development for Brooklyn and Queens at Citi Habitats. "For instance, for a long time 4th Avenue in Brooklyn wasn't zoned for any retail, and neither was Long Island City when new developments first started coming in." All of which meant that neighborhoods seeing floods of new residents didn't have space for businesses that would serve them.

Still, there are some common causes of this particular civic conundrum. If you find yourself, say, running all your errands near your office in Midtown before heading into your own neighborhood for the evening, here are some of the reasons why:

It's a corporate numbers game

Unsurprisingly, when it comes to larger chains such as drug stores and certain grocery stores, the people making the decisions care much less about a neighborhood's growing cultural cache than they do about numbers on a spreadsheet. "If you're a real estate manager for a major retail operation, you're not necessarily driving around Brooklyn looking for signs of change," says Ken Fisher, a former Brooklyn council member, and a land-use attorney at Cozen O'Connor. "Any neighborhood is just one more place on a list of places where somebody is giving you demographic information."

"These companies are looking at density, foot traffic and median household income, which can still be very low even in areas where brownstones are selling for a lot," explains Corcoran's Michael Cardillo. "So they might be sort of late to the game, but they may be okay with that. The mindset is that they want to come in when a neighborhood is mature, or quote-unquote 'settled'."

So even if you think your neighbors would all flock to a solid drug store, grocery store, or a bank that provides an alternative to predatory check-cashing operations, corporate research numbers likely tell a different tale.

"Private services like banks and drugstores, which are dominated by national chains, by nature tend to be conservative and driven by metrics," Fisher concurs. "That's in contrast to bars, coffee shops, and galleries, which are willing to locate in changing neighborhoods because they anticipate that they themselves may become destinations. And while those types of businesses have a high failure rate, it doesn't stand to damage a national brand if they end up having to close a store. It's different for national chains."

And when in comes to grocery stores in particular, the profit margins are slim, which is why you tend to see organic foods and higher-end products popping up in delis and corner stores long before larger stores start setting up shop. "We're only just now seeing a Whole Foods in Williamsburg, and gentrification there started 20 years ago," says Kemp. "They've got so much inventory to move every day that they waited until it was a very safe bet economically." Instead, if a neighborhood looks on paper like it has lower median incomes, you'll tend to find grocery stores "pushing lower quality foods and lower price points," says Kemp.

When it comes to grocery access, the city is making some efforts to combat the problem, most notably wtih its FRESH program incentivizing the development of neighborhood grocery stores. "It's a great collaboration of city agencies trying to bring these tenants into certain areas that need it," explains Heidi Burkhart, founder of affordable housing developer Dane Real Estate.

And when an entire neighborhood is being developed or re-zoned by the city, as in the case of East New York, says Fisher, the Bill de Blasio administration has arranged for city planning to work with the office of management to allocate funds for anticipated infrastructure needs such as schools, road widenings, and parks, meaning development gets put on a much faster track than in areas where gentrification happened more organically.

There's no room to grow

In some cases, if a certain kind of business hasn't made its way to your neighborhood, the issue might simply be one of physical space.

"In Bed-Stuy, for instance, a lot of the major retail corridors like Malcolm X boulevard haven't really 'turned' yet, in part because some of these stores want a specific amount of square footage," says Maundrell. "And if that space doesn't exist, they're not going to open. So the existing real estate has to lend itself to these businesses."

"Institutional or chain retail oftentimes need larger footprints due to economy of scale," Cardillo adds. "They can't come into a typical 25x70 or 50x70 location. Instead, they wait for new developments in the area to create space to bring larger retailers in. And there's often a lag there, since developers don't come in until several years after the so-called 'pioneers.'"

For this reason—as well as the need for businesses to service newly-dense neighborhoods where developments are cropping up—retail space and public services are often baked into the plans for brand new buildings. On the retail side, an example would be Long Island City, where Maundrell says that while zoning intitially didn't allow for ground-floor retail in new buildings heading to the area, has since changed to allow retail spaces of various size to service the neighborhood. "If you're going to build 30,000 apartments, you need to support that. It's how you create a community and jobs," he says.

This same effect also applies to public services, such as parks and schools, which Fisher says are sometimes required by the city (as in the case of the Williamsburg waterfront re-zoning), or offered by developers, as happened in DUMBO, where Two Trees added a middle school to the ground floor of a new building at 60 Water Street.

Bottom line: certain kinds of businesses and services require the kind of space that only large, new developments tend to provide (if they don't already exist in the area, that is), meaning that they won't come to a neighborhood until the big-time developers show up.

The squeaky wheel

If you've ever wondered how you live on a block populated with multi-millionaire brownstone owners while the street is somehow always covered in free-floating trash, the answer may lie with your block assocation—or lack thereof. Though the city should, in theory, service all neighborhoods equally, in practice, it tends to be the squeaky wheel that gets the grease.

"It really varies from neighborhood to neighborhood and sometimes even block by block," says Fisher. "Even in areas that have suffered economically in the past, Crown Heights, for example, there were still blocks with very strong block associations and a lot of participation. And some community boards and elected officials are more focused on that type of constituent service [for example, street sweeping and other quality of life measures] than others."

"It's likely that if these things are a problem, your local elected officials are pushing for quality-of-life efforts," says Julia Vitullo-Martin, a senior fellow at the Regional Plan Association. "Community boards and neighborhood groups have to do it, and also neighborhood officials."

"It's about being the squeaky wheel," says Fisher. "There often gets to be a tipping point where enough complaints filter up that the government changes its behavior, but there can be a lag time on that." This can even be an issue in wealthy, well-established areas like Brooklyn Heights, Fisher notes, where new garbage cans haven't been brought in to accommodate all the new foot traffic from Brooklyn Bridge Park, creating more trash on the streets. "At some point, enough people will notice and start complaining, and the city will address that," he says.

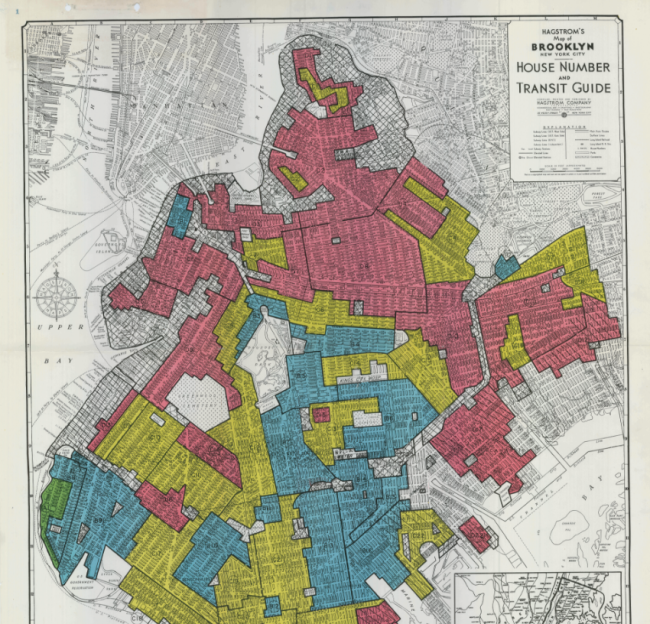

Of course, there are larger socioeconomic forces at play here as well. While services and basic infrastucture improvements will generally go to the neighborhoods that are the most vocal about demanding them, many neighborhoods that are just-now gentrifying were sunk into neglect by deliberate, often racist policies such as redlining, a practice that systematically herded people of color into certain neighborhoods them cut them off from services and devalued their properties. And these areas will often continue to get ignored until a wealthier demographic moves in and starts agitating for improvements—for example, the pearl-clutching shock of many relatively new north Brooklynites at the poor quality of the G train, a transit line that was largely ignored for years because it exclusively served the outer boroughs before the areas became trendy.

And unsurprisingly, Fisher notes, while these types of quality of life concerns are relatively quick for the city to address, upgrades such as bus service, additional bike lanes, or new schools take even longer to get moving.

And of course, in any changing neighborhood, the addition of new, improved services can be a double-edged sword when it comes to affordability and maintaining a neighborhood's character. "For the community it can become a case of 'be careful what you wish for,'" says Burkhart. "Where there's progression, there's always going to be that kind of bell curve where you hit the top and everything's perfect, then it starts going down for long term residents, and there are too many big box stores."

Meaning that if you want neighborhood services to go along with your high cost of living, unfortunately, you'll be facing down a real estate Catch-22.

**This article originally ran on November 7, 2016.**

You Might Also Like