How did Long Island become so segregated—and what can be done about it?

Recently, a t-shirt designed by students from Oceanside High School drummed up some controversy in the Long Island town. The shirt, Patch reports, created by a group of friends for an annual "Senior Cut Day," included a number of racial slurs and epithets. The school quickly distanced itself from the shirt, emphasizing that it had no part in its design, but locals took to social media to express their disgust. One person wrote, "I hope you realize the community won't stand for your intolerance."

I grew up in Oceanside and graduated from Oceanside High School. And while my graduating class thankfully remained scandal-free, I wasn't terribly surprised by the story—my hometown, and many like it on Long Island, is overwhelmingly white (over 90 percent, according to the 2010 census), and despite its proximity to New York City, as well as Long Island's overall diversity, the region is highly segregated, which is especially apparent in its public schools.

At least in my experience, this can create a collection of self-contained bubbles in which there's little contact between people from different backgrounds. And the separations are striking: According to The Atlantic, affluent Garden City is 88 percent white, while Hempstead, directly to the south, is 92 percent black and Latino.

It seems like intolerance is a part of life for many on Long Island. So how did the region get to a point where, 60 years after Brown versus the Board of Education, towns and public schools are still starkly divided?

The history

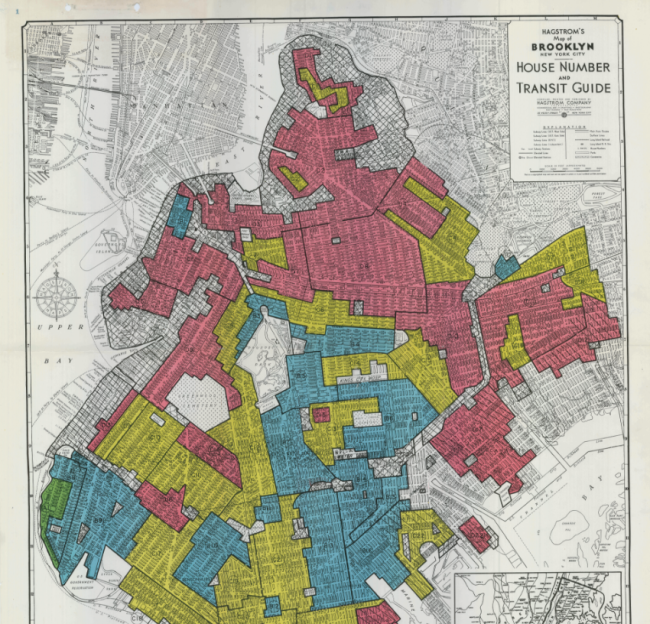

Long Island's segregation did not develop in isolation; instead, it is reflective of a nationwide reality that sprung from decades of discriminatory housing policies.

Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law, described in an interview with NPR how people of color were historically hindered from owning homes in places like Long Island, and kept separate from whites by the federal government. During the 1950s, he explains, the government subsidized homes in the suburbs that had deeds forbidding resale to African-Americans. He points to Long Island's Levittown, perhaps the most famous example of a post-World War Two planned suburban development, as an example of how these racist policies were perpetuated. The developer of the town, Levitt & Sons, was able to build thanks to loans from the Federal Housing Administration—on the condition that leases barred those who were "not members of the Caucasian race."

This blatant form of housing discrimination was officially outlawed with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, which prohibits basing the sale or rental of a home on a person's race, nationality, religion, or gender. But the sharp divisions persist on Long Island—Levittown, for instance, remains 89 percent white.

John Logan, a professor of sociology at Brown University who has written about segregation in America's suburbs, says that even after the FHA, suburbs historically resisted building affordable housing. "If they did allow apartments, they'd often build studios instead of two or three-bedrooms," which made it more challenging for lower income families to move in, he says.

Rothstein tells NPR that by the late 1960s, segregation was already deeply entrenched in America's suburbs, and its consequences continue to reverberate despite anti-discrimination legislation. As for Levittown, he says, "Those homes sold for about $8,000 a piece or $100,000 more or less in today's currency. African-Americans, working class families could have bought those homes. Today though, those homes sell for $300,000, $400,000... In the ensuing two generations, the white families who moved into those homes gained that $200,000, $300,000 in equity appreciation."

He goes on to explain that because people of color didn't benefit from that appreciation, today, "African-American incomes on average are about 60 percent of white incomes, but African-American wealth is about 5 to 7 percent of white wealth."

It doesn't help, either, that unfair housing practices persist on a more stealthy level in many Long Island communities. In 2013, for instance, Garden City officials were found to have violated the Fair Housing Act in their attempts to block the development of affordable housing, the Long Island Press reports. And recently, a lawsuit forced the town of Yaphank to change bylaws that limited home ownership to people of German descent.

Segregation on Long Island today

Logan published a report in 2014 that found that across the board, American suburbs are becoming more diverse--but no less segregated. The overall population of suburban areas is growing, Logan found, and the number of white, black, Asian, and Latino suburbanites has grown over the past thirty years.

However, he writes, "Suburban diversity does not mean that neighborhoods within suburbia are diverse. As is true in central cities, minorities are fairly highly segregated among suburban neighborhoods." For instance, he found that in 2010, African-Americans comprised about 10 percent of the suburban population, but lived, on average, in neighorboods that were over 35 percent black. Moreover, this isolation did not depend on income; affluent African-Americans lived in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates than low-income whites did.

Logan attributes this to a phenomenon he calls constrained choice. "Minority households who move into mostly white neighborhoods often find that there's not much of a welcome. They don't make friends easily and their children don't make friends easily in school. So they notice there's a cost to being the 'pioneer' minority settlers in the white neighborhood," he says. "This is one reason why you'll see a black household earning more than $75,000 living in a poorer neighborhood than a white household earning $40,000."

And those neighborhoods that are primarily non-white also tend to have higher taxes and lower rates of increase in property values, he adds. An ERASE Racism report found that poorer districts with lower home values would have to tax residents 6.5 times more than affluent ones in order to fund public school education at the same levels. And according to the think tank Empire Center, the lowest effective property tax rate in New York State can be found in super-wealthy Southampton. In Islandia, meanwhile, a town in the same county that is less white and affluent, it's the highest.

Logan posits that fear is a significant factor behind persistent racial divisions. Logan notes that many white families moved to Long Island in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s from NYC neighborhoods where they felt "forced out" by the arrival of people of color, which they associated with a decrease in the local quality of life. "Actually, quality of life [in urban areas] went down before minorities moved in," Logan says, "but these families may have more fears than people in other contexts."

Lucas Sanchez, the Long Island director of New York Communities for Change (NYCC), characterizes this as more than fear: it's straight-up racism, he says. "They don't want black and brown people living in their communities. You can't tiptoe around that reality," Sanchez says. "Many of the elected leaders are racist, too. We've advanced a little bit so people can't be as forward, but they'll say things like, 'We want to maintain the nature of our village and protect its identity.'"

On Long Island today, racial divisions are particularly evident in the public schools, which seem to be growing more segregated over time rather than less. ERASE Racism, a Long Island non-profit that promotes racial equity in housing and education in the region, found that over the past 12 years, the number of "intensely segregated" school districts--those that are 90 to 100 percent non-white--has doubled.

This seems to have a snowball effect of furthering segregation. A report conducted by the Center for Understanding Race and Education at Teachers College found, via surveys and interviews with Long Island homeowners, that there is a strong correlation between school districts perceived as "bad" and the number of non-white students that matriculate there--which drives affluent, primarily white home buyers to purchase in majority white neighborhoods with "good" schools.

"Inequalities get built in very deeply," Logan says. "There's a persistence to the pattern once it's established, and things that keep it going."

How some advocates are trying to address the problem

Several advocacy organizations are taking on Long Island's deeply entrenched segregation problems. ERASE Racism, for instance, through its inclusive housing initiative, has been working to expose incidents of housing discrimination on Long Island, and reinforce anti-discrimination laws.

Last year, in cooperation with the Fair Housing Justice Center, the organization sent testers to an apartment complex in Commack, and found that management misled prospective black renters, but not white ones, about the availability of units. They successfully settled a lawsuit against the complex for violating the Fair Housing Act. Another advocacy organization, Long Island Fair Housing, spearheaded the lawsuit in Yaphank against the town's restrictions on non-German-American homeowners.

And Sanchez says that NYCC has made fighting segregation a top priority. "As we were doing all this housing work--supporting tenant associations, taking on exclusionary housing, looking for systemic solutions to foreclosure--we wondered how to tie all these things together. How do we give purpose to the work we're doing?" he says. "We came up with anti-segregation--Long Island is the most segregated suburban area in the United States."

Sanchez points to policies that perpetuate segregation, like Nassau County spending funds from HUD on projects like beautification rather than affordable housing, and allowing municipalities to use exclusionary zoning to keep affordable units from being built; furthermore, Section 8 tenants report that it's extremely difficult to find landlords on Long Island who will accept their vouchers, a problem that's rampant here in the city, as well. To draw attention to these issues, NYCC produced a report called Invisible Walls that delineates the "epidemic-level housing crisis" that persists in the region, 50 years after the Fair Housing Act.

Beyond awareness-raising, Sanchez says NYCC and organizations like it are doing on-the-ground work: "We're mobilizing low-income folks of color to call officials on Long Island out for their persistent racism and refusal to join the 21st century."

You Might Also Like