After the shipping industry left Coenties Slip in Manhattan, some of the biggest names in American art moved in

- ‘The Slip,’ a new book by MoMA’s Prudence Peiffer, looks at the role one block had on a celebrated group of artists

- Long before live-work spaces were legal, artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Indiana discovered the Slip's raw spaces

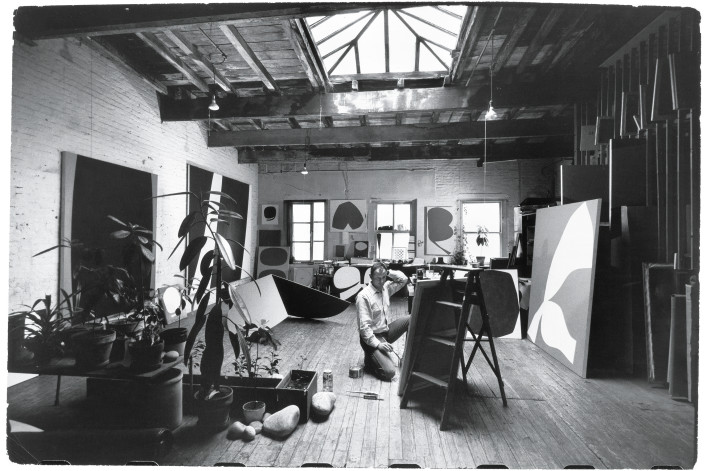

Ellsworth Kelly at his Coenties Slip studio, New York, 1961.

Photograph by Fritz Goro. Courtesy of Ellsworth Kelly Studio

Where you live and who your neighbors are play a leading role in every New Yorker’s life story. This is true today and it was true decades ago for a group of seven young artists who lived on Manhattan’s Coenties Slip, a tiny block on the East River with a view of the Brooklyn Bridge. They lived there for a little more than a decade and in that short time their work electrified the art world.

In the 1700s and early 1800s, when shipping was at the center of the city’s economy, Coenties Slip was its busiest hub. (Think of a slip as a parking space for a ship—the street that leads to it is called a slip as well.) In the 1950s and ’60s, when the seven artists moved to No. 3-5, 25, and 27, the Slip was no longer used by the shipping industry. Abandoned warehouses, gas works, and ship-chandleries were the only reminders of its glory days.

In her book, “The Slip: The New York City Street that Changed American Art Forever,” Prudence Peiffer, a writer and editor who specializes in modern and contemporary art and is the managing editor of the creative team at The Museum of Modern Art, tells the remarkable story of how this dead-end cobblestoned street lined with dilapidated warehouses became the epicenter of the American art world, where wildly diverse works of sculpture, painting, assemblage, drawing, fabric art, and collage were created.

Peiffer’s subjects are Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana (born Robert Clark), Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, and the married couple, Delphine Seyrig and Jack Youngerman. Though not a visual artist, Seyrig was an actor well-known in Europe for appearances in films directed by Alain Renais and Luis Bunuel. The artists arrived in NYC by boat from Europe or by bus from out west

Lenore Tawney, who began her Coenties Slip stay making fabric art, was an exception. She drove her Daimler from Chicago loaded with her cat, a fridge, a small bed, espresso machine, and loom.

Most of these artists were young and had little or no money (Tawney was the exception) and were just embarking on careers without any idea of where their journey would take them.

Peiffer describes this unique community as one of “collective solitude.” The artists didn’t live communally but were still closely connected. What was important to them was “knowing that there are others around you—above and below, just down the block—who are also trying to work out how to make something compelling and how to survive while doing that. But also knowing that you are alone and free,” she writes.

Hunting for a place to stay

When the artists first came to New York, they needed a place where they could live and work. They used the old-fashioned way to find an apartment: Word of mouth. They asked around at art supply stores, downtown restaurants and any other places where artists might hang out. Betty Parsons, the iconoclastic painter, dealer and collector, helped with the search and was a tireless advocate for the artists.

Live-work spaces were not legal

At the time it was illegal to live and work in the same space but that is exactly what these artists wanted to do. Undaunted by zoning laws, they moved into some of the large, empty spaces on the Slip. Some of the largest ones had been ship chandleries and places where sails were made and repaired.

Youngerman moved into No. 27 and took the top two floors that had once belonged to a sail maker. He worked on the top floor and his living space was on the floor below with plenty of room for his young son, Duncan, to play. He cut a skylight into the ceiling of his studio, had tatami mats covering the floors of his living space and the family’s meals were at a picnic table that they had bought from Sears Roebuck.

Since the spaces were so raw when the artists moved in, they made them their own, often with very little furniture, no plumbing, no heat, and, as one artist said, “wooden floors so rough that you always got splinters when you walked on them.” Peiffer points out that the absence of furniture had nothing to do with a deliberate minimalist aesthetic; they just didn’t own very much. By necessity everything was DIY and often jerry-rigged. Indiana’s space had been divided up into separate rooms using particle board so he tore the walls down and used the board as canvases when he didn’t have enough money to buy the real thing.

But, the price was right—they paid $35-$45 per month. Those numbers are shocking by today’s standards: An 800-square-foot, one-bedroom rental at 2 Coenties Slip was listed in May for $3,750.

When the artists left the Slip in the mid-'60s, the historic buildings around them were being demolished and high rises were taking their place. Peiffer captures a part of NYC history that was very nearly erased.

Following are excerpts from an interview with Peiffer a few days before the publication date of her book in July.

Why did you decide to write 'The Slip'?

I had heard of this funny-sounding place—Coenties Slip— but didn’t know a lot about it. When Ellsworth Kelly died I reached out to Robert Indiana to talk to him about Kelly. He showed me a photo from their time together on the Slip. A biography of Agnes Martin had come out about the same time and I realized that nothing had been written about these artists living in one place.Things were changing so rapidly in post-war New York and it seemed like such an interesting moment. New York’s downtown was transitioning, going from a maritime center to a financial center. Its shipmaking profile was being rapidly replaced by skyscrapers. The art world was exploding in the ’60s and in the ’70s and ’80s collecting art became a major industry. I wanted to capture this time and place in a book.

Who is the audience you were writing for?

That’s an interesting question. I was writing for a general audience. Both art history and New York history are important to me and I wanted others like me to know the stories around this moment in art. I wanted the reader to be able to see the place, to smell it, to feel what the artists felt. I wanted to tell the real estate story of the time, to have the reader picture the artists living among the sailors, the card sharks, the homeless and the canal boaters. When Youngerman told me about how he scraped the ceilings of his loft and how hot it was, I wanted the reader to feel the heat.

Clearly you did a tremendous amount of research for the book. What was most helpful?

I used many sources that are all listed in the notes section at the end of the book but what I loved most were the unexpected places where I found the wonderful little details. The letters and journals of the artists were excellent sources for these. Indiana kept a detailed daily journal, Kelly kept one that was full of sketches and notes and Seyrig wrote volumes of letters to her parents. An example: In one of Seyrig’s letters she describes a new craze sweeping the town—growing avocados from pits in a dish of water with little toothpicks holding the pit up. Remember that? I wanted to create a sensory experience for the reader and these little details are what made that possible. Rosenquist wrote an amazing autobiography that was a great help, too and Duncan Youngerman, Jack’s son, let me use his mother’s letters and shared some of his collection of personal photos with me.

How long did it take to write the book?

I can tell you that exactly. I started it when I was pregnant with my oldest child who is now seven. I was working a full-time job and had two more children before I finished it. I had time for little else as you can imagine. When the pandemic eased and the book was finished, I wrote to my friends apologizing for my absence over all those years and told them how much I looked forward to finally seeing them again!

How does the Slip look now?

Pretty much totally different. Only one building, No. 3-5, is standing. All the rest were demolished in the artists’ time. For a while, some of them lived in a demolition zone. Robert Indiana writes about looking out his window and seeing gaping holes in surrounding buildings.

The cobblestones are still there and the streets around the Slip are still narrow but I had to remind myself, when I visited there, how near they were to the river before the slip was filled in. At one time, Herman Melville liked to walk to the Slip and look across the river to Brooklyn. Did you know that he mentioned the Slip on the opening page of Moby Dick? “Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip and from there, by Whitehall northward.”

There were many other artists and writers who were inspired by the Slip. Who were some of them?

There’s a long literary history that Indiana cites a lot in his artwork. Walt Whitman wrote about the ferries coming in at the end of the Slip and as I said, Melville cites the Slip in the first page of “Moby Dick.” He also mentions the Slip in his novel “Redburn” written a few years before “Moby Dick,” where he describes its “grim” warehouses and how the main protagonist sat on the wharf and watched the ships leave the slip.

What drew the artists to this piece of the city?

The rent was incredibly cheap and the spaces more open and, because of their previous commercial use, offered more flexibility for creating a work/life area that traditional apartments didn’t. Most of the least expensive apartments in Manhattan were often in a long railroad configuration. Not what the artists needed. The neighborhood of the Slip was secluded and near great places to walk and be re-inspired. Walking the Brooklyn Bridge and taking the Staten Island Ferry were some of the ways the artists cleared their heads. They loved being so close to the water. And it was where they were able to live according to the concept of “collective solitude” which is a model governed by the place and its architecture.

Several of the artists were gay in a time when homosexuality was both illegal and demonized by many. Do you think that these artists felt safer living under the radar on the Slip?

The Slip offered a safe harbor at a time of entrenched homophobia. And a place where people could be whoever and whatever they wanted, without having to conform to any societal ideals. In a moment where the stable nuclear family was being used as a kind of political tool against the encroachment of communism, and where homosexuality was illegal, it was a place that wasn’t policed for this. Artists could live as they wanted. Even to be a woman living alone and not in a boarding house or hotel for single women the way Martin and Tawney did, was unusual.

Tell me a little about the interaction between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs involving the Slip.

Well, I didn’t expect to have Moses or Jacobs appear in this story but they ended up being central to its final section. As president of the 1964 World’s Fair Corporation, Moses was a key figure in tapping Philip Johnson to design the New York State pavilion and to commission artists to make works for its exterior. Johnson chose Indiana, Kelly, and Rosenquist. At the same time, many of Moses’s development policies for Downtown were already impinging on or directly threatening the area around the Slip. There’s a lot of irony that this person who was in part responsible for the artists’ biggest stage and audience up to that point was also the figure who was taking away their homes. Jacobs’ activism, which is what stopped some of the most egregious plans by Moses for downtown, was so crucial to the Slip.

Is there a neighborhood in New York today that is similar to the Slip?

It really was such a unique neighborhood, because of its siting at the edge of the city, its past as a waterway and a street, as such a central commercial hub and as an obscure, unknown destination. The slips hosted so many itinerant communities—the sailors on shore leave who’d stay at the Seamen’s Church Institute, the canal boaters who once crowded the Slip’s waters, and the artists who knew, when they moved to the Slip, that theirs was a precarious real estate situation. So, nothing similar. And it might be hard to find a river-view loft for $350 or $450 a month, the 2023 equivalent of the $35-$45 the artists were paying!

You Might Also Like