Sparks fly at fiery City Council hearing on broker fee bill

- Thousands of brokers showed up to protest the Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses (FARE) Act

- City Council Member Julie Menin told audience members multiple times not to disrupt the debate

- Elected officials lambasted the administration for not having a bigger presence at the hearing

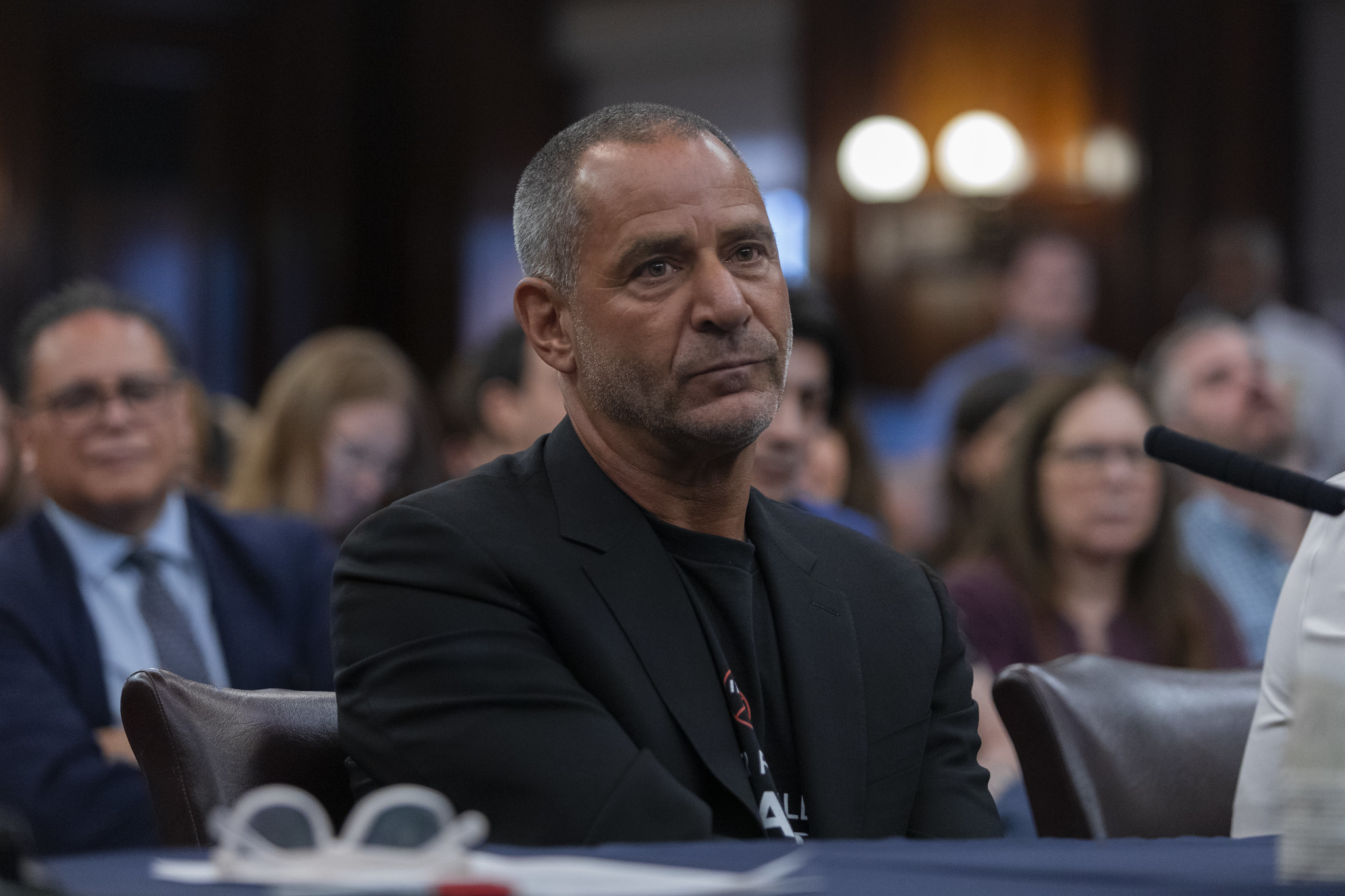

City Council Member Chi Ossé gave opening remarks about the bill at the contentious hearing.

Photo Courtesy: Emil Cohen/NYC Council Media Unit

Real estate brokers and tenants flooded the New York City Council’s chambers on Wednesday to debate one question haunting the city’s rental market: Who should pay the broker fee?

The answer, at least for now, is usually the tenant. But on Wednesday brokers, city officials, and renters sparred over a contentious bill from City Council Member Chi Ossé that would change that norm. The bill—dubbed the Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses (FARE) Act—would require whoever hires an apartment broker to pay for their services.

“We suffer under this system of forced broker fees,” Ossé said on Wednesday. “The FARE act would end this abuse and be an economic boon to the five boroughs.”

Over 400 people signed up to testify during the fiery 10 a.m. hearing, according to Council Member Julie Menin, who chairs the NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. Notably absent were representatives from the NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP), the agency that would likely enforce the law, Ossé said.

Council Member Sandy Nurse and Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso criticized the administration for not making a bigger showing at the hearing.

“This is disgusting,” Nurse said to HPD First Deputy Commissioner Ahmed Tigani, who testified at the hearing in lieu of the DCWP and did not take a position on the bill. “I’m livid right now because I’m a tenant. A lot of people in this room are tenants … We are desperate, and you have come here with nothing to offer, not even a substantive debate.”

[Editor’s note: The 10 a.m. hearing lasted six and a half hours and finally wrapped up at 4:30 p.m. on Wednesday afternoon.]

Brokers turn out to block the bill

And yet, the debate went on. And on, well into Wednesday afternoon.

A panel of executives at major real estate agencies—including Bess Freedman, CEO of Brown Harris Stevens; Gary Malin, COO of the Corcoran Group, and Hal Gavzie, executive vice president of residential leasing at Douglas Elliman—testified against the bill, arguing that landlords would just raise rents if they had to pay for the broker they hired.

“Many of these agents are renters themselves,” Freedman said. “Simply put, this bill will make it harder for brokers to be fairly paid, raise housing costs and limit housing access.”

Freedman was among the thousand of agents who spoke out against the bill at a rally outside the city council building just before the hearing organized by the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY).

REBNY has organized its members against the bill, arguing that it would raise rents. (Ossé argued Wednesday that the FARE act would not actually raise rents, because if a landlord could raise a tenant’s rent, they would have already).

Gavzie also argued that the bill could make it harder for tenants to find apartments if landlords decide not to pay fees to advertise them online. Malin said the real problem is a lack of incentives for housing development in the city—to cheers from the audience. Others argued that tenants would end up paying the fee on open listings, where multiple brokers try to rent an apartment.

But not every broker was against the bill. Independent broker Jeffrey Hannon said he’s in support of the bill because landlords can better afford to pay the fee. Anna Klenkar, a broker at Sotheby’s, worried that the real estate industry’s attempt to block the FARE act would just “erode agents’ reputations and the public’s trust.”

“The FARE Act does not cap agent commissions,” Klenkar said. “If our incomes drop because landlords pay us less than they expected tenants to pay, it just shows that the current system is built on exploitation.”

Politicians, union reps, and tenants voice their support

Politicians, union representatives, and even one venture capitalist also voiced their support for the bill, arguing it would make it clearer when tenants need to pay a broker fee, which can range from 10 and 15 percent of an apartment’s annual rent.

“If I’m not contracting you I shouldn’t be paying for your services,” Nurse said. “It is a very simple concept.”

NYC Comptroller Brad Lander called the FARE Act a "common sense" bill and urged the council to pass it. So did Allia Mohamed, the CEO of apartment listing service openigloo, and Brendan Griffith, the chief of staff at the NYC Central Labor Council, which represents 300 local unions across New York.

Brokers chase after tenants for fees because it’s easier to get a bill from a tenant than a landlord, who has lawyers, staff and resources tenants don’t, argued Rob Solano, the executive director of housing advocacy organization Churches United For Fair Housing. (Some audience members shouted “liar” after his comments. Menin had to shush the crowd multiple times).

At the same time, renters are not equipped to negotiate a broker fee, because brokers ultimately control access to the apartment, said real estate broker Michael Corley.

That was the experience of one Queens renter, who detailed through a translator how high moving costs—including broker fees—are a heavy burden on her and her family’s budget. Another renter said brokers never warn her ahead of time that she has to pay the fee.

Even venture capitalist Bradley Tusk showed up over Zoom to push for the bill, arguing that broker fees put up an “artificial barrier” to getting the “best and brightest” people to move to New York City. He previously said he would spend $25,000 on digital ads to push the bill.

He’s not the only person looking to push the bill online. Ossé reintroduced the bill in February and took to social media to push it, even appearing with comedian and Broad City star Ilana Glazer in a video to rally his supporters. (That video drew angry comments from some brokers during the Wednesday hearing).

Past attempts to change fees

Ossé first introduced the bill last year, where it again faced significant opposition from REBNY. But the FARE Act isn’t the first attempt to curb broker fees.

The New York Department of State briefly paused renter-paid fees in early 2020 under its interpretation of a landmark law—the 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act—but later changed its guidance. And 2019 legislation that would have capped fees at a single month’s rent failed to pass after facing pushback from the real estate industry.

Public Advocate Jumaane Williams said on Wednesday that he supports the FARE Act, as opposed to past efforts, because it doesn't block broker fees or cap them. It only requires whoever hired the broker to pay for their services.

Separately, the state has cracked down on broker fees. The New York Department of State reached a settlement with NYC brokerage City Wide earlier this year, where the firm agreed to pay $260,00 for excessive fees, including a $20,000 commission on a rent-stabilized apartment on the Upper West Side in 2022.

What’s next for the bill?

The Consumer and Worker Protection Committee still needs to vote on the bill, followed by the entire council before it can be sent to the mayor to sign the bill into law.

If Adams decides to veto the bill, the Council could still pass it into law with a two-thirds majority vote. Ossé said his bill currently has 33 sponsors in the 51-member City Council, one away from a veto-proof majority.

Ossé previously told Brick Underground that, if the bill passed this year, it would likely go into effect for NYC renters in 2025.