Green upgrades to help your building reduce flooding from extreme weather

- Plant a green roof or install a water-retaining 'blue' roof to capture stormwater

- Create a rain or bioswale garden to minimize flooding at street-level

- Collect water in rain barrels or cisterns for irrigation or other purposes

Zeckendorf Towers, a condo development in Gramercy Park, overlooks a 17,000-square-foot green roof by Urbanstrong that includes shrubs, perennials, trees, succulent groundcovers, and moss.

Alan Burchell, Urbanstrong

It doesn't take a superstorm like Sandy to wreak havoc on New York City. Extreme rainfall events like the record-breaking, late-September 2023 deluge flooded subways, basement apartments, and streets across the five boroughs.

As this "life-threatening event" (per Governor Kathy Hochul) made all too apparent, the city's valiant efforts at mitigating the risk of flooding and managing stormwater runoff are a drop in the proverbial bucket of the measures needed to keep New Yorkers and properties safe in the face of severe weather conditions due to climate change.

Still, the NYC Department of Environmental Protection's ongoing green initiatives provide a blueprint for co-op and condo buildings to follow in doing their part—and reports suggest that the cumulative impact of many participants taking small but significant steps is the most realistic path forward.

[Editor's note: This article was originally published in January. We are presenting it again as part of our summer Best of Brick week.]

According to a spokesperson for GrowNYC, a nonprofit environmental advocacy and educational organization, "We know that in our fight against climate change, it is collective action between everyday New Yorkers, city communities, elected officials, and public and private organizations that will ultimately make lasting change and secure a safer future that benefits all of us."

It's important to note that new developments are required to comply with green infrastructure requirements under the Unified Stormwater Rule of 2022.

"The USWR also has implications for existing buildings, especially those considering substantial renovations or retrofitting," says Alan Burchell, principal of Urbanstrong, which has offered consulting, financing guidance, custom design, installation, and ongoing maintenance of green roofs for co-ops, condos, and private residences (as well as schools and commercial buildings) since 2014.

"For properties undergoing 'significant' redevelopment, there's a requirement to manage stormwater more effectively on-site," he says, adding that this might necessitate retrofitting the buildings with features like rain gardens, permeable pavers, and green roofs.

There are other reasons to implement these features, too. "Local Laws 97 and especially 92/94, which are now coming into effect, are really driving the conversation about green roofs and/or rooftop solar," Burchell says. Local Laws 92 and 94 require new buildings and buildings replacing their roof decks to install a sustainable roof surface.

Besides helping reduce the risk of flash floods, stormwater management keeps runoff—and the pollutants it carries from roofs, streets, and other structures— from entering the sewer system and public waterways.

Here are four ways you can help your building—and the city—deal with future catastrophic storms and other climate-related issues. Of course, you'll have to cough up the funds to finance these capital improvements and make a cost-benefit analysis when determining which projects you take on. But there are grants and incentives that can help offset at least some of the costs, and the benefits are both immediate and long-term.

Create a green or blue roof

Lush rooftop gardens are not just a value-added amenity for residents. These "green roofs" are also an important element in the climate-change-fighting toolbox, absorbing rainwater, helping to slow runoff, providing insulation against the cold, and combatting the so-called heat island effect (when urban settings have higher temps than outlying areas).

Green roofs also improve energy efficiency to help you comply with Local Laws 92/94 and 97 (especially if you add solar panels) and improve your ESG (environmental, social, and governance) score.

To spur the proliferation of green roofs, the city has established a one-time, year-long tax abatement for qualifying buildings—namely, those with more than 50 percent of eligible roof space devoted to vegetation and other parameters stipulated by the NYC Department of Buildings.

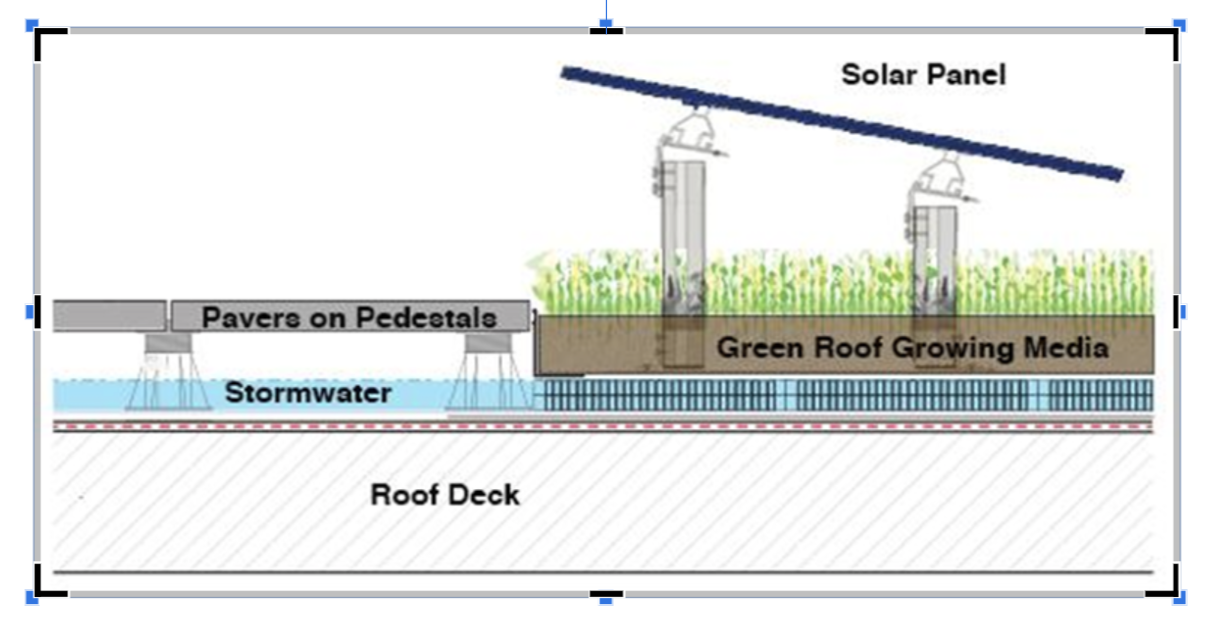

If planting and maintaining vegetation is not in the cards, you can opt for a "blue roof," which is a rooftop detention system that temporarily stores rainwater and then gradually releases it.

"We've been offering ‘blue roofs’ for several years now," Burchell says. "We’re very passionate about them, especially compared to the default grey infrastructure approach for on-site stormwater management involving cisterns and sub-surface storage tanks, which are costly to procure and install and are very singular in function."

He says that overall, blue roofs are the most cost-effective way to manage on-site stormwater in terms of dollars invested (for design, procurement, installation, and operation) per gallon managed. "Unlike with cisterns, a portion of the water sitting up on a roof can partially evaporate under the heat of the sun before the rest of it is released down to the sewer for processing. This is true even for water detained/retained on a green roof."

He points out as well that a blue roof can be incorporated into just about any other plans your building had in mind for your roof (e.g. green roofing, solar, amenity decking, concrete paver decks, rooftop garden, etc.).

Add rain gardens and bioswales

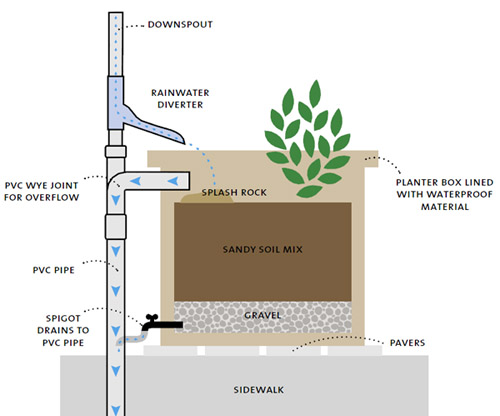

Rain gardens—aka rainwater harvesting systems—are shallow-dug, vegetative areas that collect rainwater run-off from roofs, streets, sidewalks, and other structures. A bioswale is essentially a narrow version of a rain garden (picture a trench) that can work in even tight urban spaces; in NYC, the terms are used interchangeably. Both of these structures are typically planted with native shrubs, perennials, and grasses that can withstand both drought and occasional flooding.

Leading the way are the hundreds of community gardens, which are credited with diverting some 165 million gallons of runoff from sheds and nearby buildings a year from the city's streets and sewer system, as cited in The New York Times.

The NYC Department of Environmental Protection has also been embedding rain gardens in sidewalks—you can spot them by a black metal fence with the bright blue DEP garden marker and a thirsty tree, among other plantings.

Besides absorbing some of the rainwater into the ground and slowing runoff, rain gardens also act as filters, removing chemicals and other pollutants that would otherwise enter storm drains or flow into nearby waterways. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that rainwater runoff accounts for 70 percent of all water pollution.

Other than during and after a storm, rain gardens typically remain dry, draining within 48 hours, so no mosquito concerns. The key is to choose the right plants and to locate them in the best spots.

The NY Department of Environmental Conservation even recommends creating a "mini" rain garden with potted plants, placing them near downspouts and sinking them into the ground when possible, though (per the linked resource page), "even on pavement they will still do some good."

GrowNYC has created a handy (free) Green Infrastructure Toolkit with detailed drawings and material lists that you can use as a starting point. There are also separate how-to guides for rain gardens, downspout planters (see below), and green roofs.

The NYC Department of Design & Construction also offers a video tutorial on how to construct a rain/bioswale garden.

"Our team has extensive experience with bioswales, but mostly in the Midwest where property is cheaper," Burchell says, adding that bioswales make less financial sense in places like Manhattan except for on sidewalk bump-outs and tree pits.

On the other hand, "bioswales are probably the best on-grade stormwater solution (if space allows) because you get filtration, plants, biodiversity, and pollution abatement," he says, "and you can design them with a depth of six, eight, 12, all the way up to even 36 or 48 inches deep," he says.

Use permeable pavers or porous concrete

Take another cue from the city by ripping out existing concrete or asphalt and installing materials that allow stormwater to seep into the ground—pollutants are filtered out during this process. You may have noticed this Green Initiative program on your street.

The most notable example includes the $16.6 million project that helped rebuild a popular corridor in Rockaway Beach, Queens, that was hit by Superstorm Sandy; this (literally) groundbreaking use of porous pavement is expected to allow an estimated 1.3 million gallons of stormwater to be absorbed back into the ground instead of flowing into the sewer system.

Basically, the area is excavated to a two-foot depth and backfilled with gravel to allow infiltration. Then it's topped with porous concrete or asphalt or permeable pavers for a more decorative result—such as in your building's common outdoor spaces, including a landscaped rooftop deck or green roof.

According to GrowNYC, it's important to work with a structural engineer when going this route, as porous/permeable materials cannot bear the same load and should be limited to parking or foot traffic.

Burchell says permeable pavers are not necessary on green roofs.

"An integrated blue-green roof is great for maximizing the stormwater benefits of a roof. Stormwater retention cells can be installed beneath the green roof. Also, wood deck tiles and concrete (or porcelain) pavers on pedestals have sufficient cracks and gaps between them to allow water to trickle down to the blue roofing system below," he explains.

Get a rain barrel or cistern

In addition to the above, or if none of those steps are practical, you can use rain barrels or cisterns, which are designed to capture rainwater for irrigating a green roof or rain garden, as long as you are not growing plants for food. This "grey" water can also be used for hosing down outdoor spaces, thereby lowering your water bill.

The upright vessels range in size from 50 to 60 gallons to hundreds of gallons and are most often connected to a downspout with a diverter, though a freestanding barrel placed near a roof or other structure also helps. All models have a mesh cover to screen out debris and a spigot on the side for filling watering cans or hooking up to a hose. Most are sturdy plastic, which is easiest to clean and withstands freezing temps.

According to GrowNYC's rainwater harvesting how-to, the size of your tank should be based on the surface area of your building's roof, which determines how much water can be collected, and how much water is needed for gardening or other purposes.

Generally, rainwater systems can collect approximately 0.5 gallons of water per inch of rain. For example, a 20- by 40-foot roof will

collect approximately 800 gallons of water from one inch of rain.

Pricing starts at around $50 for foldable models that can easily be stored during dry spells and winter. Basic 60-gallon barrels by Eartheasy cost around $160.

The city is even partnering with local elected officials in holding rain barrel giveaways throughout the five boroughs.

Of course, as Burchell points out above, green/blue roofs are more efficient—and you'll be "maximizing the utility of unused rooftops for improving quality of life, creating revenue, improving energy efficiency, complying with local laws, boosting property values, protecting the lifespan of the existing roof structure, growing food, promoting biodiversity, and reducing the ecological footprint—all at the same time, if desired," he says.

One final recommendation: Regardless of which firm you go with, a design-build scenario is more cost-effective and promotes accountability, Burchell says.

"Having one vendor install someone else’s work and then maybe yet another firm be responsible for ongoing maintenance just opens the doors to unnecessary blame and finger-pointing," he says.

Sign Up for our Boards & Buildings Newsletter (Coming Soon!)

Thank you for your interest in our newsletter. You have been successfully added to our mailing list and will receive it when it becomes available.