The cow in my kitchen: A quest to install a new gas stove gave me an electrifying epiphany

- A New Yorker is shocked to learn her gas stove produces about the same amount of pollution as a cow

- Upgrading her 1959 co-op to support an electric stove turns out be too complicated and expensive

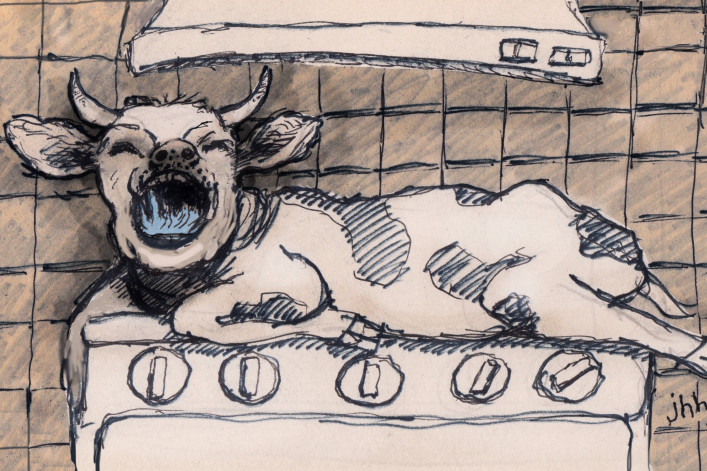

Like a cow, a gas oven can be expected to belch out an average of 210 pounds of methane a year.

J. Henry H. Lowengard

Once upon a time it was a simple thing to replace a stove in your kitchen. You stop by the appliance department at Home Depot, Lowe's, PC Richards, Topps Appliance City, or AC Madison and pick out a nice one. Then hand over your credit card and choose a delivery date. The delivery/installation guys show up, disconnect your old oven, and plug in the new one. They also haul away your old stove. You tip the guys 20 bucks and by suppertime you were cooking—literally.

Life is far more complicated these days. New York City is pushing buildings to switch to electricity for heating and cooking and move away from environmentally harmful gas. Now, in part due to the dangers in messing with increasingly aged gas lines, arranging to have a new gas stove installed in a NYC apartment—be it a condo, a co-op or a rental—takes some determination.

Until recently, I was totally ignorant of all this. Anticipating a Thanksgiving cook-a-thon, I decided to replace my 26-year-old workhorse of a GE gas oven. While the stove still worked, it was somewhat fatigued after its many years of good service. The LED controls had faded to a point that setting the timer or temperature involved a lot of squinting, careful head-angling, and bright lights.

I found a promising new range at Home Depot; like my previous model it was made by General Electric. It was a sleek, 30-inch-wide, five-burner gas range with a self-cleaning convection oven and air fryer in stainless steel. All at the friendly price of $848. I looked forward to the installation of the last stove I ever planned to buy.

But getting my old stove out and the new one in turned out to be significantly harder than I anticipated, and along the way I had an electrifying epiphany.

The super knew the drill

Before I made my purchase, my first move was to consult my building's superintendent. As he handed me a Xeroxed sheet with the names of local plumbers, he informed me of the new rules. I would need to hire a master licensed plumber, arrange for a Department of Buildings filing, and submit a certificate of insurance. This was much more of a rigmarole than I anticipated.

I entreated my sister to take a detour through the appliance department on a visit to Home Depot. They didn’t know about the master licensed plumber rule or DOB filings, but were sure I could find someone through the store’s referral service. I went online, filled out a form, and was immediately besieged by texts and phone calls from plumbers who expressed interest in taking care of my installation—at varying prices.

Calling all master licensed plumbers

One offered to do it at the friendly cost of $198. But when I asked him to email me a copy of his master plumber license he stammered and confessed he was merely a licensed plumber. Another candidate bid $980 to do the job but again could not verify his license status. I called the three plumbers referred to me by our super.

One followed up with an offer to do the work for $1,906.31 (tax included). His estimate dictated that the stove must be unboxed before his arrival and that the service did not include moving my disconnected stove to the basement. As this bid was more than double the sticker price of the new stove, I continued my search.

Next I approached my co-op's management company, opening a completely new can of worms. They insisted I would need to submit an alteration agreement with associated fees including a $1,250 security deposit and $600 in nonrefundable processing charges, on top of whatever the plumber might want for his labors.

There was more: I was told (mistakenly, it turns out) I would need to upgrade my electrical panel to allow for a 220-volt line; submit the scope of work to the building’s engineer for review, the cost of which would be my responsibility; retain a licensed master plumber to cap the gas line properly; and submit COIs from each contractor and an executed contractor indemnification form. YIKES!

A simple plug-and-play job?

Clearly, our managing agent had missed the point that this was a simple (in my humble opinion) plug-and-play operation. Thus, it was up to me to convince them that I was not swapping out my gas stove for an electric one, merely upgrading what I already had. But it did plant a bee in my bonnet.

Eleven emails later they confirmed the requirements matched what the super had told me days earlier: All that was required was a certificate of insurance, a copy of the master plumber’s license, and proof that a DOB filing had been executed.

Then, the lightbulb went on. Could it be all these requirements were trying to tell me it was time to go electric?

Greening energy use in NYC

I was vaguely aware of the NYC’s new regulations, including Local Law 154, which bans the use of fossil fuels (which means gas stoves and heating systems) in all new construction of residential buildings that are seven stories tall. It takes effect in 2024 and as of 2027, will apply to all new residential construction regardless of size. Turns out, a similar law passed statewide in May 2023, which goes into effect for smaller buildings in 2026 and taller ones in 2029. In place of gas-powered stoves, furnaces, and propane heating systems, Local Law 154 incentivizes use of heat pumps and electric stoves.

Then there’s Local Law 97, an aggressive plan by NYC to require most buildings over 25,000 square feet to reduce their carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050. Buildings like my co-op face fines if emissions are over the limit—as of right now, they are.

My first instinct was, “Ewwwwww, but who wants to cook with electric heat? I did some research. Turns out, maybe I do.

That’s because after digging into the matter, the evil nature of fossil fuels began to creep me out. Apparently, I don’t even have to turn on my stove to produce an invisible cloud of methane in my kitchen—it leaks out of my stove whether it’s on or off, accompanied by plenty of other nasty greenhouse gasses as well. It’s not just the environment I’m damaging, it’s my own health.

Bessie in my kitchen

In fact, the level of pollutants coming from my gas stove is roughly equivalent to keeping a cow in my kitchen. Home on the range (in cattle country, that is), Bessie can be expected to belch out an average of 210 pounds of methane a year. The Bessie in my kitchen emits not only methane but also nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and formaldehyde, not to mention benzene, xylene, toluene, and ethylbenzene—gasses and chemicals that like war, are not healthy for children and other living things. The only difference seems to be no milking is required of my Bessie-the-range—a dairy-free disadvantage, as I see it.

Sadly, according to the super of our vintage 1959 building, there’s not enough power in the building to rewire a single, much less all 201 apartments to support an electric stove setup. I checked out a few DIY videos on YouTube. Not for me, but if it’s your thing, please don’t forget to turn off the power before you start! So, for now, Bessie’s going to have to stay lassoed to my kitchen.

Thanksgiving came and went. I am abandoning my new quest for a new stove until the day when I can replace it with a sleek, new, greenhouse-gas-free induction stove. Someday, just not today. In the meantime I’m going to try and use my toaster oven, microwave, and electric kettle to minimize use of Bessie in my kitchen. And maybe I’ll ask Santa for a plug-in induction cooktop as well.

Mary Lowengard is a writer and editor who has been in a New York State of mind since 1971. She recently published a collection of essays about owning and fixing up a country house,“The Bucknoll Cottage Chronicles: Sex and the City meets Under the Tuscan Sun, but no sex, no city and in the Poconos." The title says it all.