Looking back at Harlem's history as a major Jewish enclave

116th Street in present-day Harlem. Many churches, like the one above, were once synagogues.

Photo courtesy of Yeshiva University Office of Communications and Public Affairs.

Nearly 40 years ago, Jeffrey Gurock, now the Libby M. Klaperman Professor of Jewish History at Yeshiva University, wrote When Harlem was Jewish, a book about the Jews who lived uptown from 1870 to 1930. Now Gurock has released his second tome about the neighborhood, The Jews of Harlem: the Rise, Decline and Revival of a Jewish Community, which takes up where the last one left off “with lots more anecdotes and fewer numbers” than the first.

Enrolled in a Ph.D. program at Columbia University, Gurock chose Black-Jewish relations as his dissertation topic. His mentors advised him that to truly understand his chosen subject, he needed to focus his research on the place where the two groups lived together. All he had to do was look out of his window and there was his perfect subject--Harlem. After decades of research, fascination and involvement with that neighborhood, Gurock is delighted to be known as “Harlem’s Jewish Historian."

Here are five things about Gurock’s Jewish Harlem that you may not have known before:

1. More Jews once lived in Harlem than anywhere else in America.

In 1917, Harlem was home to the second largest population of Jews in America and the third largest in the world—about 175,000 strong. The Lower East Side and Warsaw were the only other communities that could claim more Jews than Harlem, with approximately 350,000 Jews and 343,000 respectively.

Gurock explains the demographics of the area: “In East Harlem, the Jews shared the neighborhood with Italians (LaGuardia was their District Leader and Congressman). In Central Harlem, the population was German—both Jewish and non-Jewish."

"North of 125th Street was the early black enclave,” he says. As of 1920, 70 percent of Manhattan’s 107,000 Blacks lived in Harlem; in the 1920s an additional 175,000 moved in.

How the two groups got along is a complicated story. "There is no one Jewish story pre-World War II," says Gurock. "There were some Jewish real estate operators in the early decade of the century who tried with their Christian counterparts to keep blacks out of the neighborhood. At the same time, pre-World War II, almost the entire white population in the black areas was Jewish. Jews showed no special disinclination to living with African-Americans."

2. Before 1930 there were two distinct Jewish Harlems.

One was East Harlem (which Gurock defines as 96th Street and the East River to Fifth Avenue, north to the Harlem River); the other was Central Harlem (110th Street to 125th Street, Fifth Avenue to Morningside Avenue).“ The further you moved westward, the better you were doing.”

Gurock says that Central Harlem was the home of the hero of Abraham Kahan’s 1917 bestseller, The Rise of David Levinsky. The titular character was a poor immigrant boy from Russia who made his way to America and the Lower East Side, became wealthy in the garment center, moved up to Harlem to an elegant apartment overlooking Central Park.

East Harlem was the home of a very different kind of Jewish family and the example Gurock chooses was quite real: Gurock’s own paternal grandparents. As he explains, they lived in a tenement at 100th Street and Park Avenue where their four sons shared one bed.

3. Two of present-day Harlem’s most imposing church buildings were once synagogues.

Central Harlem, before 1930, had 40 to 50 synagogues, some quite formidable; East Harlem had about 150 smaller ones. Those in Central Harlem that still stand have since been converted to churches but Jewish symbols are still visible on some of their facades.

Two of the most historically significant synagogues in the neighborhood stood across the street from each other on West 116th Street between Fifth Avenue and Malcolm X Boulevard. Ohab Zedek, which is now on the Upper West Side, is probably best known for hiring Yossele Rosenblatt, the man considered to be the most famous cantor who ever lived. Rosenblatt appeared as himself in the first talkie movie, The Jazz Singer, after having refused to play the role of Eddie Cantor’s father.

The Institutional Synagogue was built diagonally across from Ohab Zedek, at 37 West 116th Street, and was the first synagogue in America to have a community center complete with a pool, an art room, and more. The founders’ intent, according to Gurock, was to get people “to come to play and stay to pray”.

Ohab Zedek is now the Harlem Baptist Temple Church and the Institutional Synagogue is now the headquarters of the Salvation and Deliverance Church.

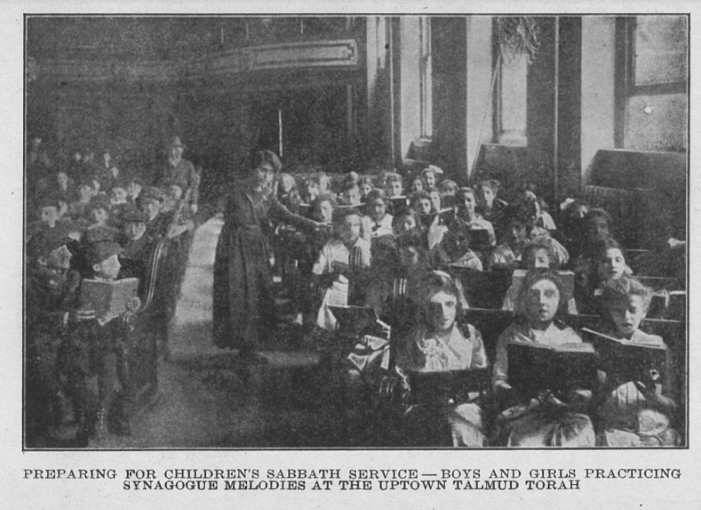

Students at the Uptown Talmud Torah, circa 1917 (The Jewish Communal Register of New York City, 1917–1918).

4. Some the 20th century’s most prominent Jews lived in Harlem.

One of the first Jewish residents of Harlem was Benjamin Peixotto, sent in 1870 by President Ulysses S. Grant as his envoy to Bucharest and charged with expressing America’s antipathy to Romania’s persecution of the Jews.

Many of the other influential Jews who lived in Harlem in the first quarter of the 20th century were involved in one way or another with show business. The list includes Oscar Hammerstein I, cigar-maker-turned-Harlem-real-estate-developer who owned the Harlem Opera Theater on 125th Street and was the grandfather of Oscar H II, George and Ira Gershwin, Milton Berle, Fannie Brice and Sophie Tucker. Gurock says that Al Jolson “hung out in Harlem” although he never actually lived there.

Baseball player and World War II spy Moe Berg, who was born in Harlem, may qualify; a film about his life is currently in production with Paul Rudd in the starring role.

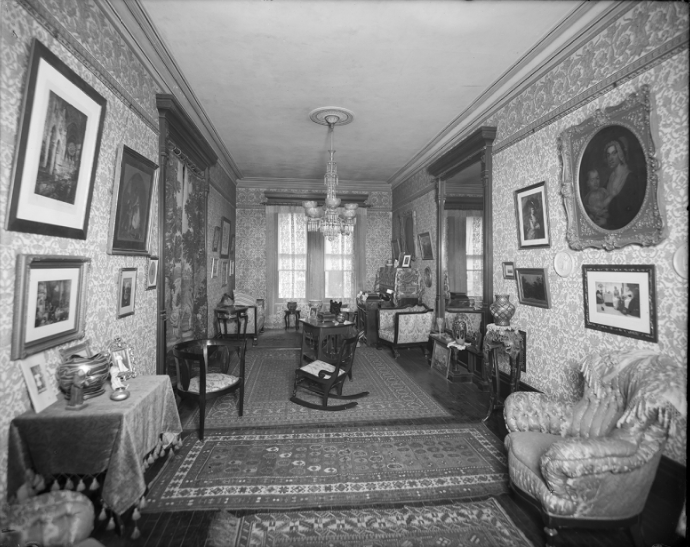

An elegant parlor in a Jewish home in Harlem, 1912 (photo courtesy of Museum of the City of New York)

5. Jews are returning to Harlem—whether Judaism will do the same is still unknown.

According to the 2010 census, there are now more Caucasians than African-Americans in Harlem. Some of the families who have lived in Harlem for generations feel threatened by the gentrification of their neighborhood, which has brought on new, expensive stores and high rises, and seen the demolition of some African-American institutions.

One outspoken Harlemite, Michael Henry Adams, wrote an essay in the New York Times last year entitled "The End of Black Harlem." He writes:

"For so many privileged New Yorkers ... Whole Foods is just the corner store. But among the black and working-class residents of Harlem, who have withstood red-lining and neglect, it might as well be Fortnum and Mason. To us, our Harlem is being remade, upgraded and transformed, just for them, for wealthier white people."

One question Gurock has—and he says that it is too early to know the answer—is whether the Jews who are part of this growing number will do more than just move to the neighborhood. “Will they bring with them Jewish institutions-or build institutions-synagogues and schools—the way the Jews of the early 20th century did? Will Judaism come back to Harlem along with the Jews?”

But no matter their race or religion, those moving to Harlem are facing real estate prices that seem to just keep climbing upward.

Gurock quotes an ad in a circa-1896 ad in a Yiddish newspaper for apartments at 1883 Third Avenue, between 97th and 98th Streets, for “young couples and growing families.” It offers “practical, decorated three-room apartments"—what would be a one-bedroom now—for $8.50 to $9.50 a month.

Central Harlem apartments were much more expensive. An ad from 1901 for the elegant Graham Court, landmarked and still standing at Seventh Avenue and 117th Street, offers six- to 10-room apartments for $1,000 to $2,000 a year or $83 to $166 per month.

A one-bedroom in a building not far from the Third Avenue apartment would now cost somewhere between $800 and just under $3,000 per month. The most recent rental in the Graham Court was a three-bedroom priced at $4,975 per month.

You Might Also Like