Get to know NYC's mysterious Hart Island

In addition to popular day trip destinations like City Island and Governor's Island, New York's waterways are also dotted with more mysterious, less accessible spits of land. One of these is Hart Island, which is just a fifth of a mile big and has been home to some fascinating—and heartbreaking—history, and has recently become a bit more reachable, reports WNYC. (You can listen to the segment below.)

Today, the tiny island that sits just north of City Island in the Long Island Sound is overseen by the Department of Corrections as a potter's field—that is, a burial place for a million of New York's unknown and sadly unclaimed. Its present-day stillness is at odds, though, with its complex and occasionally turbulent history.

A cemetery from the beginning

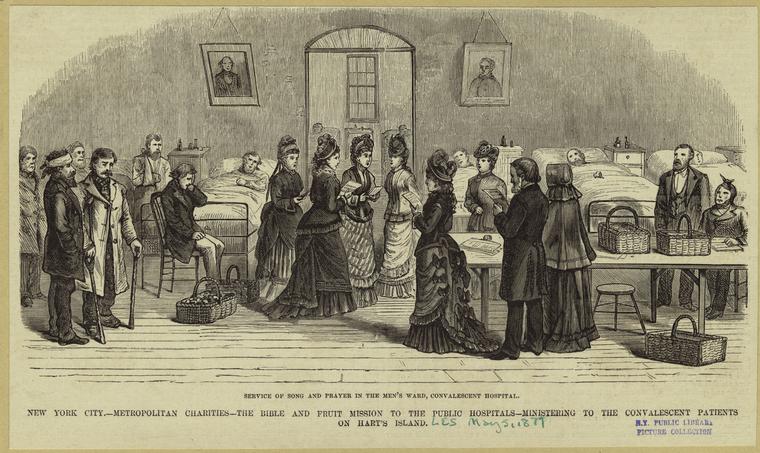

According to the DoC, the island was purchased in 1868 as a place to inter the bodies of anonymous or poverty-stricken New Yorkers; that first year, it became the final resting place of 1,875 people. That wouldn't be all, though: later, Hart Island would play host to a Civil War prison camp for captured Confederate soldiers, hospitals for poor women and for those suffering yellow fever, a mental institution, and a jail for prisoners working on the island. Prior to World War II, Hart Island also housed a senior citizens home and a jail for delinquent boys. During the Cold War, the Army used a portion of the island as a missile base; in the 1970s, a drug rehab center had a facility there.

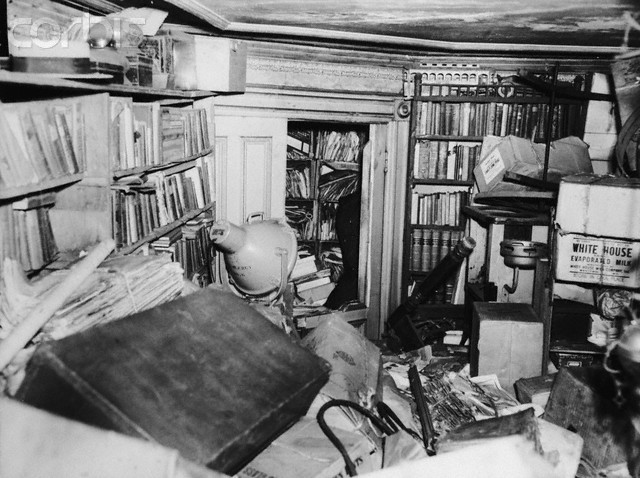

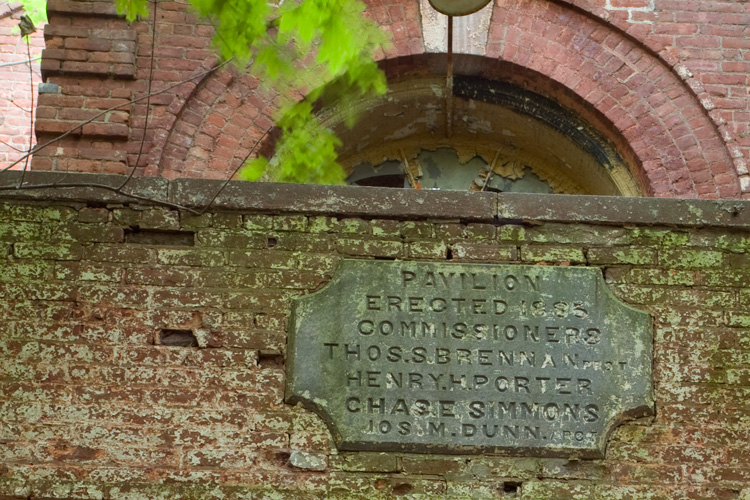

Although Hart Island was off-limits to civilians for decades—as Gizmodo explains, the island was closed to the public in 1976, after the rehab center closed—some intrepid urban explorers still found their way there. Richard Nickel, Jr., who in his Blogger profile describes himself as a "Guerilla Preservationist," paid a visit to the island in 2008. He captured images of its derelict buildings, including the Pavilion, an insane asylum for women built in 1885.

Now, the island has returned to its original purpose as a graveyard for the forgotten and the indigent. Inmates from Riker's Island are hired—for 50 cents an hour—to bury the dead who were never identified, became wards of the state, or came from families that couldn't afford funeral expenses. Artist Melinda Hunt began The Hart Island Project to uncover some of their stories, using data culled from GPS and public databases, as well as information submitted by families of the buried. The Project was given the film below, from a 1990 VHS recording of inmates at work on the island, which provides a somewhat disturbing look at the burial process.

The island opens up

In May, the New York Times wrote about a few of the New Yorkers interred on Hart Island, including homeless children and mentally ill individuals who fell under the state's guardianship. In many cases, family members of the deceased were dismayed to learn where their loved ones ended up; a friend of one woman, whose identification seems to have been mistakenly swallowed up in city bureaucracy, described her burial on the island as "criminal."

Relatives and friends of Hart Island's dead had little recourse until 2012, when the city began permitting family to make monthly visits to a gazebo to pay their respects. And starting last year, as the result of a class action lawsuit filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union, the city now permits gravesite visits for family members, and provides free ferry service once a month from City to Hart Island. Members of the general public also have an opportunity to see the island, provided they schedule a visit in advance; the DoC has details here.

NPR notes that while advances in DNA technology have led to the identification of more of the deceased, leading in turn to disinterments as family members choose to bury their loved ones elsewhere, the city may soon run out of space for burials. Should this come to pass, it will need to begin knocking down the abandoned, 19th-century structures on the island to create more room, which means that history buffs and would-be explorers should try to arrange a visit soon.

You Might Also Like