Believe it or not, May 1st was once moving day for the entire city

Think your move was hectic?

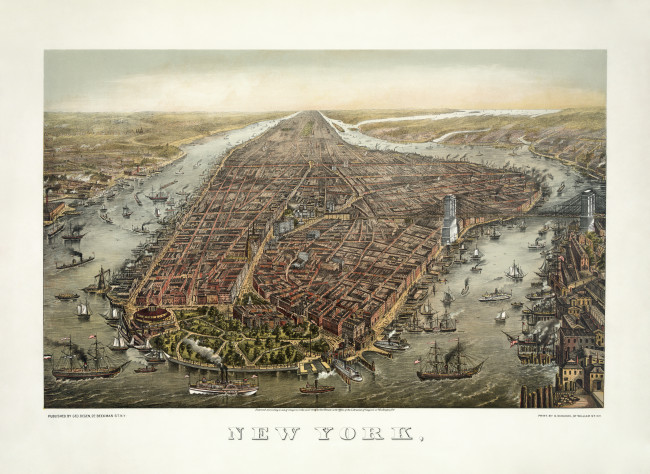

Harper's magazine, 1850/New York Public Library

Picture this: It’s May 1st in New York City. At the crack of dawn, the insanity begins: “A whole drove of Gothamites struggling amid pots and pans and pictures and rolls of carpet" are about to hit the streets according to the New York Times. As the day unfolds, every single renter in New York who's not renewing his or her lease is making the move to another apartment or house. This one day of the year was moving day for thousands of New York City residents in the 18th and 19th century, and by the beginning of the 20th century, about a million locals were switching abodes in just 24 hours. Talk about chaos.

Frances Trollope, mother of the Anthony Trollope and author of the not-very-flattering "Domestic Manners of Americans," published in 1832, experienced May Day first hand. “The city... has the appearance of sending off a population flying from the plague, or of a town which had surrendered on condition of carrying away all their goods and chattels….more than one of my New York friends have built or bought houses solely to avoid this annual inconvenience," she wrote.

[Editor's Note: A previous version of this post ran in May 2017. We are running it again in case you missed it.]

A New York Historical Society publication,"When Did the Statue of Liberty Turn Green?" describes the day as “a horror of disorder, price gouging and panic,” which began a few months earlier, on February 1, the date landlords delivered the bad news about any intended rent increase. If the tenant and landlord couldn’t agree on a rent, the apartment went on the market and residents had until April 30 to find themselves another home.

This May 1, we look back at this antiquated NYC practice.

A custom from colonial days—maybe even before

Some say the British custom of celebrating the spring holiday of May Day led to the practice of signing leases on May 1 in New York. But, according to Aleksandr Gelfand, who curated an exhibit about a decade ago on the subject of Moving Day, the first of May was chosen because that was when the Dutch embarked on their original journey to the island of Manhattan. Gelfand says that each May Day anniversary of the original journey, “the Dutch would repeat the journey by leaving their houses and seeking a new shelter.”

However it may have gotten its start, it's clear from a letter written by a Manhattan resident in the mid-1700s that Moving Day had been around for a while even then. He wrote to relatives asking forgiveness for not having written sooner—he had been busy moving from Broadway to Horse and Cart Street (wherever that may have been). “All the houses here are hired according to an old custom from the 1st of May,” he wrote. He calls it an “old custom” in the mid 1700s, which makes it seem reasonable to assume that it would have been around since the century before.

Eyewitness accounts of the chaos

Several “celebs” of the 1800s gave their impressions of Moving Day either in their diaries or their books. In a May 1 entry to the diary he kept for 40 years, prominent New York lawyer George Templeton Strong, wrote: ”Never knew the city in such a chaotic state. Every house seems to be disgorging itself into the street; all sidewalks are lumbered with bureaus and bedsteads to the utter destruction of their character as thoroughfares...“

From Trollope: “Rich furniture and ragged furniture, carts, wagons and drays, ropes and canvas and straw, pacers, porters and draymen, white, yellow and black, occupy the streetfront east to west, from north to south….”

One somewhat unexpected witness to the insanity of the day was Davy Crockett, who was driving around the city with a friend on May 1, out to see “the improvements and beautiful houses in the new part.” When they headed down Broadway, what he saw alarmed him: It looked as though “the city was flying before some awful calamity." The idea had no appeal to the rugged frontiersman: “It would take a good deal to get me out of my log-house”.

3. The movers were more that just shakers—they were often breakers.

In the beginning of the May Day ritual, the movers were Long Island farmers with wagons to rent. Eventually, the job fell to the cartmen of the city. One such cartman, Issac Lyon, who had a stand at the corner of Broadway and Houston Streets, wrote about the weeks leading up to Moving Day (as evidenced in this online collection of May Day ephemera from Baruch College): “During the last two weeks in April of each year the cartmen begin to put on a few extra airs, and look and act with more importance that at any other time during the year.”

“To one class alone is the day an era of rejoicing—it’s the cartman’s harvest,” per the Times. Families that moved risked losing some of their possessions, or at the very least, having some damaged. “Sofas that go out sound will go in maimed . . . bedscrews will be lost in the confusion, and many a good piece of furniture badly bruised in consequence.”

Another article in the Times written almost 45 years later in 1919, listed all the things that anyone making the move had to worry about. One was “how much of the furniture would reach its destination as furniture and how much as firewood.”

On Moving Day, a cartman could charge any price he pleased. Many New Yorkers had to pay as much as a week’s wages to move. Although the city fathers tried to control price gouging, movers didn’t pay much attention to the rules. The night before in 1890, the legal charges were published in the Times, and warnings were made for readers to make a contract with their mover: $2 for a load on a one-horse truck within two miles; 50 cents for each additional mile; 50 cents to load and unload on the first floor and 25 cents for each additional flight of stairs.

By 1905, Moving Day had undergone a change for the better and, per the Times that year, it was no longer “the picturesque helter skelter exciting occasion it was in the ‘good old days—modern methods have reduced the operation to a science….” In the article, one moving mogul of the day claimed that “nowadays we will move a man’s housekeeping effects in one load, unless he keeps a hotel, and assume all risk and breakage or loss..."

Not everybody hated Moving Day

There was one demographic that liked Moving Day: kids, because they were usually taken out of school for weeks to help with the move. Many New York schools declared the day a holiday so that everyone could lend a hand with the move. In a poem about a child reminding his mother to wake her up early on Moving Day, called "A May Day Madrigal," the child says: “I want to see the carpets torn in patches from the floor/ I want to see the statuettes thrown through the plate glass door.”

Moving Day comes to an end

The custom began to fade in the early 1900s as new rent laws gave tenants increased protection, and more Manhattanites decamped for new neighborhoods in the outer boroughs.

Greg Young and Tom Meyers, of the podcast The Bowery Boys, explain it this way: “The subway changes everything, basically, as did the construction of new homes in boroughs outside of Manhattan.” They quote the long defunct Evening World newspaper: “rapid transit facilities have enabled hundreds to move further out and east side landlords say they have more vacant apartments than ever before. Hence rents are cheaper and fewer are unable to pay up.”

According to Gelfand, World War II finally put an end to Moving Day. Many of the men who worked in the moving industry had been drafted. The ones who remained preferred to work in the defense industry. Then, on May 1, 1945 the custom ended.

Just for fun, we asked Nimrod Scheinberg, vice president of sales for Oz Moving, what he thinks it would be like in 2016 Manhattan if we brought Moving Day back. In a word, “a nightmare."

“Imagine how crowded the staircases, elevators and all other escape routes would be…..There wouldn’t be anywhere near enough trucks and movers to satisfy every person who needed to move...moving services would be priced astronomically high….Having to accommodate that sheer amount of movement would shut New York City down," he says.

Sounds a little like the 18th century.

You Might Also Like